The strange mystery of The Bonded Vault Heist at the Mob Bank hidden at the Hudson Fur Storage

Often regarded as the perfect heist, or the last great heist – The Bonded Vault Heist story is a strange tale of lies and betrayal within the mob during the late 1970’s.

On August 14, 1975, a sweltering summer day – especially for eight men who were stuffed into a nondescript van on Cranston Street in Providence.

Just after 8am, one of the men, later identified as Robert J. Dussault, casually stepped out of the van, dressed in a crisp light gray-checked suit and clutching a briefcase. He walked across a parking lot and through the front door of Hudson Fur Storage, a business at 101 Cranston St. Once inside, He strolled into the office of Sam Levine, one of Hudson Fur’s owners.

Barbara Oliva was nearby, moving a rack of furs through a massive vault door when she heard Levine call for and his brother, Abraham, into his office.

“I just thought that they wanted Mr. Levine into the office, so I started walking away,” Oliva recalled decades later in an interview with Target 12. But Dussault stopped her. “Oh no,” he said. “You, too.”

“Why?” Oliva asked.

That’s when Dussault pulled out the handgun and pointed it at her face. “Because I said so,” he replied.

Dussault had Levine summon two other workers from their rooms, then sat all five inside Levine’s office and put pillowcases over their heads.

It was then that Dussault’s six accomplices lumbered out of the van and into Hudson Fur. The masked men carried drills, crowbars and enormous duffle bugs. One of the bandits stayed in the van as a look-out.

But the bandits weren’t interested in valuable furs. They were after a much bigger prize.

That’s because they knew something few others in Providence did: Hudson Fur Storage housed a secret room that contained 146 huge safe-deposit boxes, each measuring two feet high, two feet wide and four or five feet deep.

The safest place New England?

There was perhaps no safer place in all of New England for someone to hide their wealth – not because of the room’s fancy alarm system, but because of the clientele that used it.

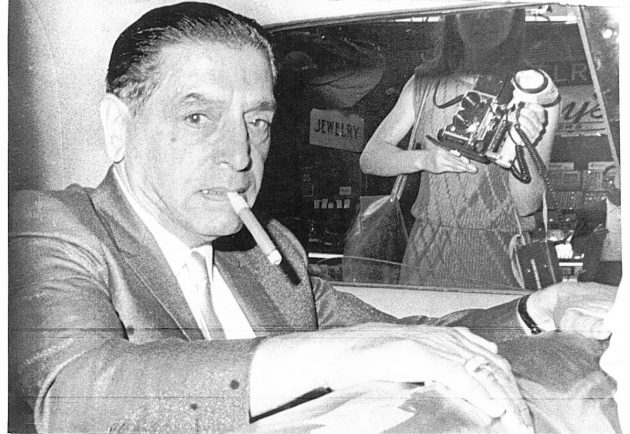

Many of the 146 boxes contained the spoils collected by the powerful organized crime syndicate run by reputed mob boss Raymond L.S. Patriarca, whose crime family ruled La Cosa Nostra in New England for more than three decades. He had an iron fist and a reputation built on violence and fear. His bookies, associates and wise guys used the boxes to hide everything from cash and guns to gold bars and jewelry.

That was the prize awaiting the thieves as they entered the room and went to work on that hot August day.

“I could hear them drilling,” Oliva said. “Then I could hear the doors, the big, heavy doors, falling to the floor, and it sounded just like sewer caps.”

As it turned out, those drills proved worthless against the locks on the safe deposit boxes. But the burglars quickly figured out they could pop the solid steel doors off their hinges using only a crowbar and a lot of muscle.

The thieves called each other “Harry” to shield their real identities, Oliva said, and as they went from box to box she heard shouts of joy coming from the vault.

“They were yelling, ‘Oh, Harry, you gotta come! You would not believe what’s in here! You just won’t believe!’” she recalled. “They were taking turns going back and forth, and they were going, ‘Holy Christ, look at all this stuff – we’ll never be able to carry it all outta here.’ ”

And that turned out to be true.

After more than an hour’s work, the man dragged out seven duffel bags literally bulging with loot. They stuffed them in the van and the trunk of a nearby Chevrolet Monte Carlo they had stationed there. The bags weighed down the back of the car so badly that it practically scraped the pavement.

Once the bandits were gone, Dussault gathered up his hostages and led them to the back of Hudson Fur at gunpoint.

“I said, ‘Uh oh, here we go – execution,’” Oliva remembered. “I said, ‘I’m never going to see my babies again.’”

Dussault crammed the five hostages into a small, dank bathroom and jammed a chair against the door. He warned them that if they didn’t wait five minutes before trying to get out, they would be gunned down in cold blood.

Mob Bank

No one knows exactly how much was taken in the heist. (After all, the type of people who rented those safe deposit boxes were not about to file an insurance claim or a tax return.) The original report suggested $1 million, Public records from the trial claim around $4 million in cash and valuables.

However law enforcement for years has believed the take was far greater – probably at least $30 million, perhaps more.

Oliva said that figure would not surprise her considering what the thieves didn’t bother taking.

On the day of the robbery, a detective brought Oliva into the room to give her a look. She was ordered not touch anything.

“It was knee-deep in money, silver bars, gold bars, raw gems, guns, machine guns, chalices,” Oliva recalled. “It was unbelievable.”

And again, that was just what the men left behind.

Later that day, the bandits regrouped at 5 Golf Avenue in East Providence, where one of the gunmen – Charles “Chucky” Flynn – had rented a house.

They divvied up the loot and each took a bag full of cash – “the disposables,” in the words of Wayne Worcester, who covered the story as a Providence Journal reporter and is now a journalism professor at the University of Connecticut.

“They each got a grocery bag full of $64,000 figuring that later on – and this was the agreement – they were going to split the take from jewelry and silver ingots and gold coins,” said Worcester.

Who would rob the mob?

It turned out that the really valuable loot – gold bars, top-quality jewelry and rare gems – was given to none other than the alleged mafia boss Patriarca himself, according to interviews with retired FBI agents and others directly involved in the case.

At the time of the crime, that revelation surprised investigators because the people who lost valuables in the robbery were the same bookmakers, associates and wise guys who paid homage to Patriarca. Why would he move to punish his own men?

“Patriarca had just finished serving a prison sentence and came home to find the revenue that he should have made in his absence apparently was not quite what he thought it was,” Worcester said. “It either meant that someone was skimming from him while he was in jail, or his people were lying down – and either way he couldn’t let that happen. He wouldn’t let that happen.”

Detectives with the Rhode Island State Police and Providence Police tried to connect the dots of the robbery back to the Mob boss.

But no solid evidence that Mob boss Raymond L.S. Patriarca, who controlled organized crime in New England from a storefront on Atwells Avenue, approved the heist of the secret Mob bank in Providence has ever been discovered.

Originally posted 2016-12-16 13:06:48. Republished by Blog Post Promoter