How can the Internet remain a great enabler of innovative growth (global public good) and not become a dangerous ‘digital Bermuda Triangle’ (global public bad)?

This important question in digital politics will be addressed during this week’s Global Conference on Cyberspace, at The Hague (16-17 April), the upcoming Malta Conference on Internet as Global Public Resource (29-30 April), as well as many other discussions taking place over the next few months (see the 2015 timeline of events).

Digital/net/cyber/e/virtual politics – including the above question – can be broadly explained using 3 triangles:

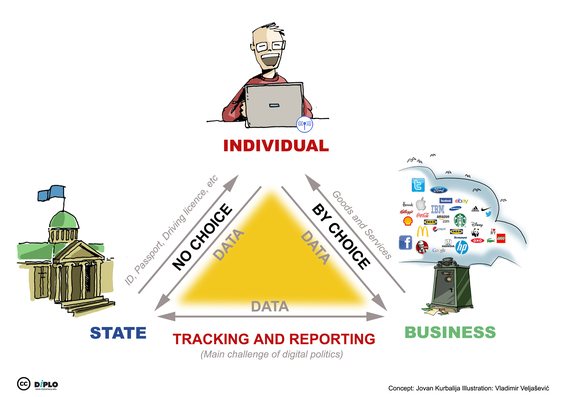

The first triangle depicts the main flow of digital data involving individuals, states, and business.

Citizens submit their data to states without any choice, in order to obtain documents, regulate tax payments, and ensure their rights. Citizens can opt out from this obligation to provide data only by leaving the country, but in the other country, they will be subject to similar requirements. Citizens submit data to businesses by choice (although it may not always be an informed one).

Most data is stored by states and businesses. The question of data tracking and reporting by states and business is a current focus of digital policy discussions. For example, after the Charlie Hebdo attack, French authorities asked the Internet industry to share data to support the fight against terrorism. President Obama made the same request during his speech at the Silicon Valley Summit on Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection (13 February). Interestingly enough, the summit was marked by the absence of the leaders of the main Internet companies (Facebook, Yahoo, Google). The next triangle provides a possible explanation of their absence.

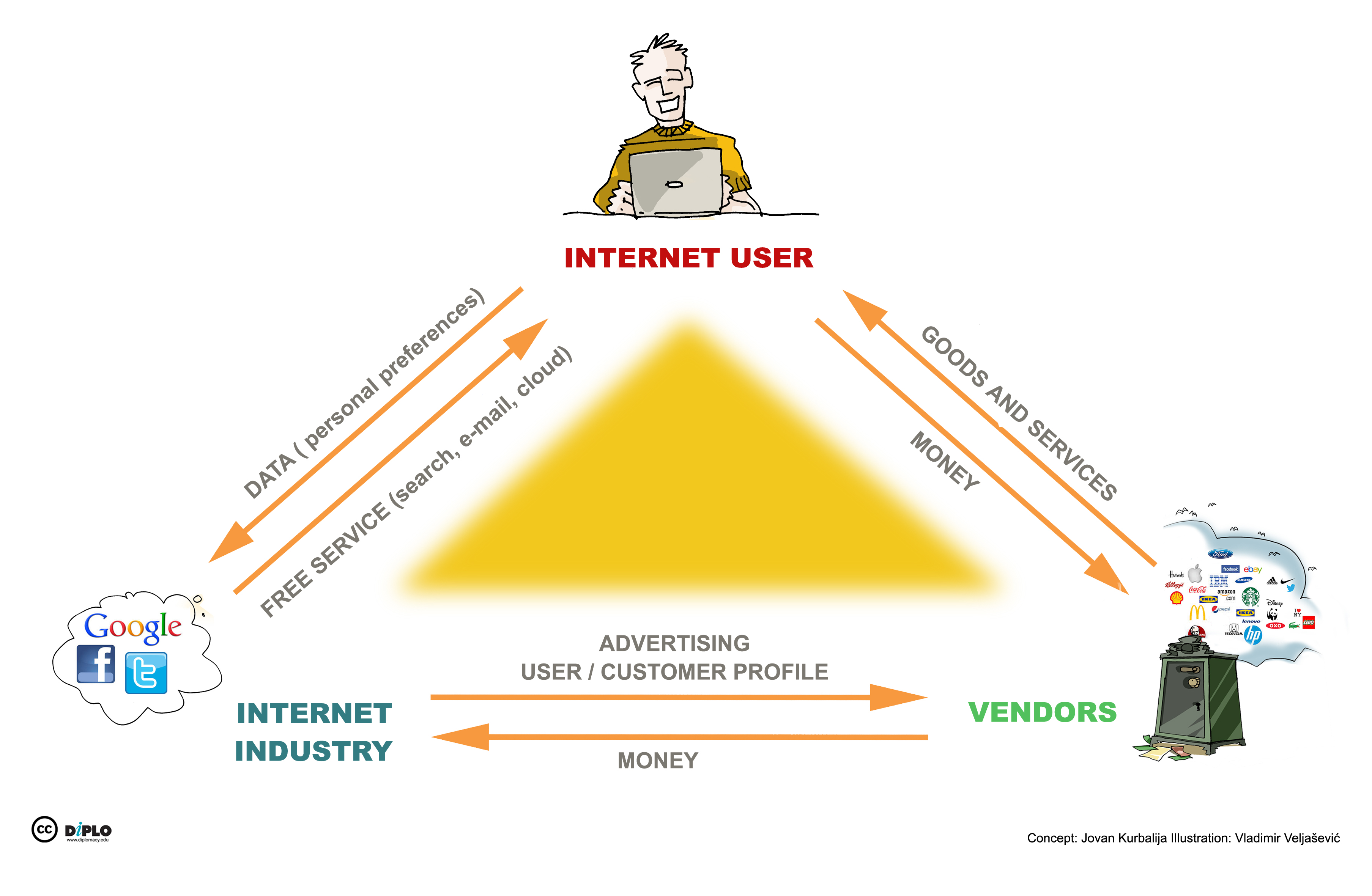

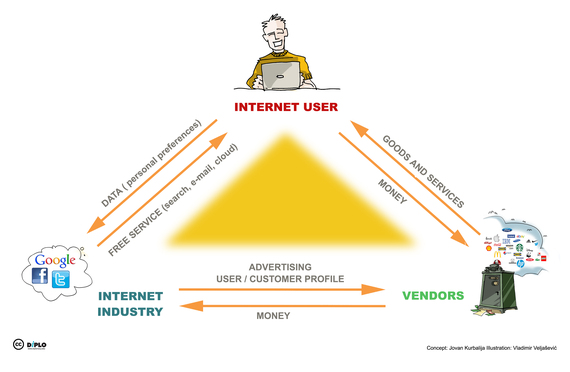

The second triangle summarises the core Internet business model that involves

- Internet users getting free Internet services in exchange for the personal data they provide;

- the Internet industry covering their operational expenses, and profiting from selling users’ data-profiles and advertising to vendors; and, last,

- vendors closing the triangle by selling their goods and services to users.

The Internet industry’s concern (and a possible reason for their absence from the cybersecurity meeting with President Obama) is that massive sharing of users’ data with governments could undermine user trust, and thereby affect business profits.

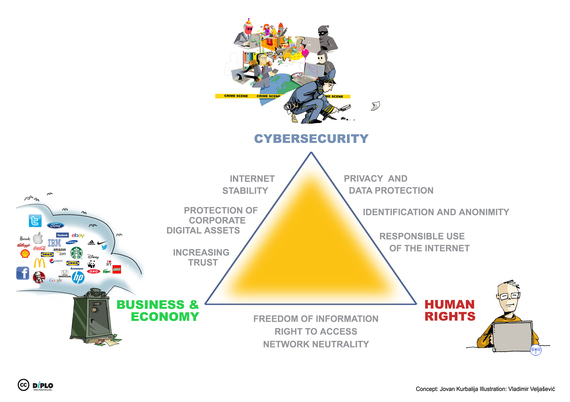

The third triangle maps out three main aspects of global digital policy: cybersecurity, human rights, and business/economy. A new Digital Social Contract or, as it is sometimes described, Digital Magna Carta, can be visualized using this triangle.

In the global debate about the design of this triangle, each actor has their own priorities: states should have the means to guarantee the rule of law and security; the individual should have the right to privacy, freedom of speech and information; and business should be able to innovate and develop their services.

More initiatives – fewer solutions?

Almost every month, there are important events discussing global digital politics. In March, UNESCO hosted an event on CONNECTing the Dots in Digital Space. After the April Hague conference, the caravan will move to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, to the Freedom Online Conference; later on to the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) Forum in Geneva, and the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) preparatory meetings. In June, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) will meet in Buenos Aires; regional IGFs will be held around the world; and WSIS negotiations will gain momentum in New York.

Today, there are close to 10 initiatives and projects aimed at creating a one stop shop, clearing house, observatory, and ‘forums’ to analyse digital policy. The paradox is that the problem of complexity is being addressed by creating an additional layer of coordination complexity. Ultimately, more initiatives and events may lead to fewer solutions. The lack of global policy solutions triggers another tendency to …

Fall back to courts

Individuals and institutions try to find solutions for their digital problems in courts worldwide. In May last year, the European Court of Justice ruled on the ‘right to be forgotten’ on the Internet. Recently, the same court discussed the legality of ‘Safe Harbour’ arrangements for data exchange between the USA and the EU. In the USA, Microsoft challenged a ruling saying that it had to submit foreign data to US authorities. And in many countries, the legality of Uber, the Internet-facilitated taxi service, has been challenged in the courts. In June 2015, the International Conference on Dispute Resolution and Jurisdiction in Geneva will discuss digital challenges for national and international courts.

Lack of effective global solutions will increase use of courts for settling digital policy issues.

What can be done?

A grand design approach would be particularly risky. Digital politics is messy, with solutions often triggering new problems. Thus, policy interventions should be made with utmost care in order to avoid solutions that do more harm than good.

We do not need to re-invent the wheel. For example, checks-and-balances, subsidiarity, and accountability are as useful for digital politics, as they have been for traditional politics. The Geneva Internet Conference (November 2014) has analysed the use of proven policy mechanisms in addressing digital policy issues (see the Geneva Message).

Another proven approach would be to consider the Internet as a global public good. This carries the advantage that while users, business, and governments have different roles in the development and use of the Internet, they share the common concern of preserving a functional and safe Internet as a global public resource (see: Malta Conference on Internet as Global Public Resource).

_______________________________

Based on the dynamics mapped in these 3 triangles, a carefully developed policy solution could reduce the risk of the Internet disappearing in a ‘digital Bermuda triangle’ of fragmentation, where conflicts could overcome the opportunities and innovation for which the Internet is known.

Originally posted 2015-10-26 07:14:05. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

Arindam loves aliens, mysteries and pursing his interest in the area of hacking as a technical writer at ‘Planet wank’. You can catch him at his social profiles anytime.