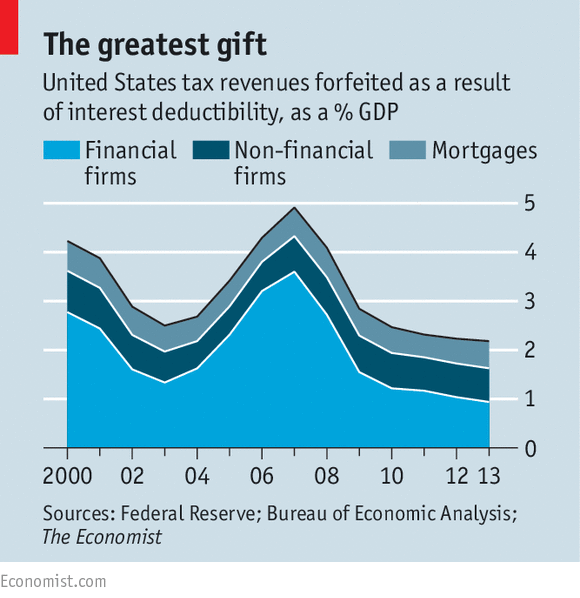

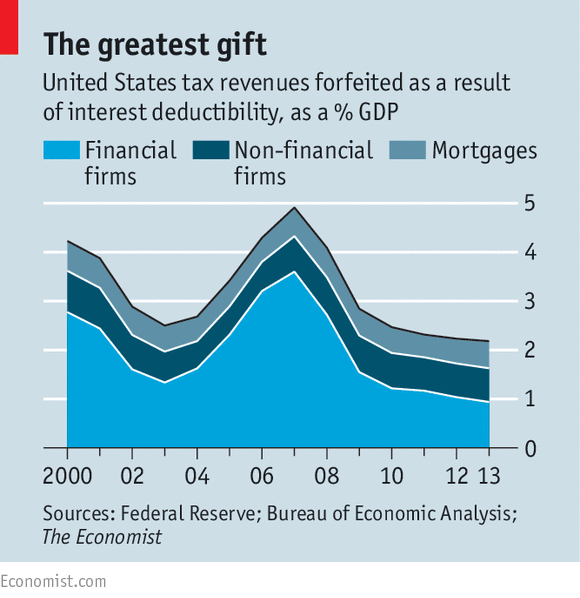

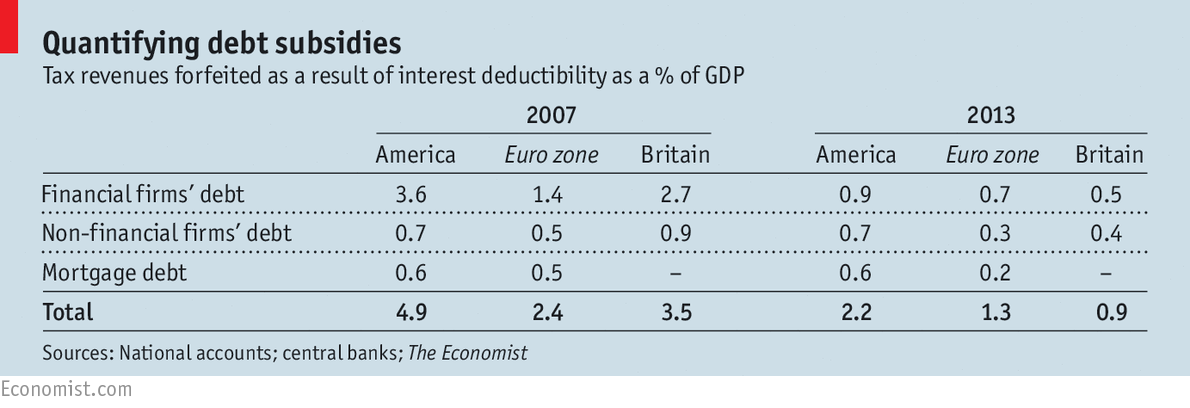

HOW valuable are tax breaks for debt? Most governments say how much mortgage-interest relief costs them in forfeited revenue. But the second type of tax break—interest deductibility for companies and financial firms—is harder to get to grips with. As the financial system has got bigger and fiddlier, no-one really knows how much interest the world’s firms pay. National accounts, the figures of publicly listed firms and the limited tax statistics that exist all give very different answers.

To come up with estimates (see table), The Economist has used national-accounts data because they should show the broadest range of activity. We make adjustments that lower the tax break’s size. We include net rather than gross interest for non-financial firms. For financial firms we include an estimate of interest paid on debt but not that paid by banks on deposits. In America we exclude partnerships and “pass-through” entities that pay no corporate tax.

There is nonetheless a lot of uncertainty about the figures. National accounts use a crude definition of “financial firm” that can include not just banks but many other entities—for example, the assets of investment funds, which may not pay corporation tax. The aggregate figures net the profits and losses of firms, and so may fail to capture loss-making firms that would not be liable for tax under any regime. Some investors who own shares are exempt from tax on dividend income. This may partly cancel out the bias toward debt at the firm level. We have not tried to capture this effect.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this exercise. First, governments need to improve their data collection. Second, notwithstanding this, it seems that tax breaks for debt today are big, even at a time of very low interest rates. If rates normalise and interest payments rise, they will balloon back to the levels last seen before Lehman Brothers collapsed.

Originally posted 2015-10-16 04:22:06. Republished by Blog Post Promoter