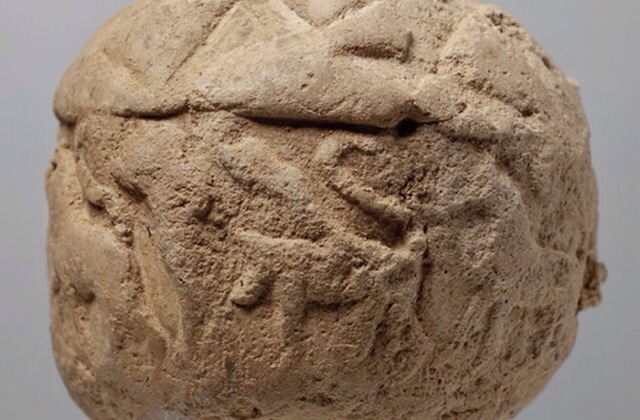

Researchers studying clay balls from Mesopotamia have discovered clues to a lost code that was used for record-keeping about 200 years before writing was invented.

The clay balls may represent the world’s “very first data storage system,” at least the first that scientists know of, said Christopher Woods, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, in a lecture at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum, where he presented initial findings.

The balls, often called “envelopes” by researchers, were sealed and contain tokens in a variety of geometric shapes — the balls varying from golf ball-size to baseball-size. Only about 150 intact examples survive worldwide today.

Researchers studying clay balls from Mesopotamia have discovered clues to a lost code that was used for record-keeping about 200 years before writing was invented.

The clay balls may represent the world’s “very first data storage system,” at least the first that scientists know of, said Christopher Woods, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, in a lecture at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum, where he presented initial findings.

The researchers used high-resolution CT scans and 3D modeling to look inside more than 20 examples that were excavated at the site of Choga Mish, in western Iran, in the late 1960s. They were created about 5,500 years ago at a time when early cities were flourishing in Mesopotamia.

Researchers have long believed these clay balls were used to record economic transactions. That interpretation is based on an analysis of a 3,300-year-old clay ball found at a site in Mesopotamia named Nuzi that had 49 pebbles and a cuneiform text containing a contract commanding a shepherd to care for 49 sheep and goats.

.

.

Originally posted 2013-10-18 22:02:31. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

![20131018-235912[1]](https://coolinterestingnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/20131018-2359121.jpg)