The Mystery of Yarmouth Runic Stone

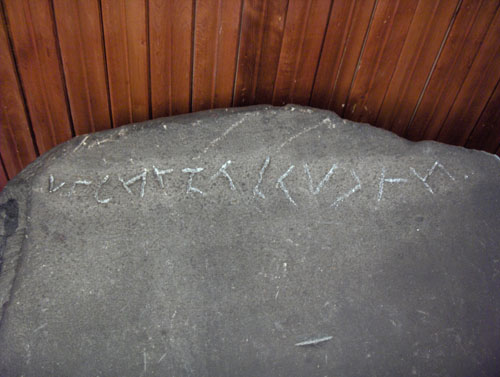

In 1812, a 400 pound boulder was found at the nearby village of Overton, Nova Scotia. It is interpreted by some people to have been carved by Leif Ericson, while others feel the markings are natural scratches gradually enhanced over the years. This runic stone was first discovered in a salt marsh by a Yarmouth doctor, Richard Fletcher. He was an army surgeon who had retired and gone to live in Yarmouth in 1809, subsequently dying there in 1819. He actually located the stone close to the shore on a point of land that then ran out between the outlet of the Chegoggin Flats and the western side of Yarmouth harbour. There are only fourteen characters in its short inscription and these have been puzzled over by the experts for close on two hundred years.

Shortly before World War I, the Runic Stone travelled to Christianna (now Oslo), Norway, where it was shown at an international exhibition. It was then taken to London, England, where it would remain in storage at the offices of the Canadian Pacific Railway, as ocean travel during the war was hazardous, and it was deemed too risky to transport the stone. It finally returned to Yarmouth sometime after the Armistice of 1918.

The stone has now been carefully preserved and advantageously displayed in the fascinating Yarmouth County Museum, at 22 Collins Street. Its Director and Curator, Eric J. Ruff, the Historian, has valuable infromation about the mysterious old stone and its possible origins. He said, “the Yarmouth Runic Stone is very interesting in the history of Yarmouth. Most people think that it was left by the Vikings but there are lots of other theories. Basically it was found towards the end of Yarmouth harbour in 1812 by Doctor Fletcher. Some people, notably the descendants of Dr. Fletcher, always felt that he did the carving. Lots of others have felt that the Vikings left the stone, and it’s been translated a couple of times by various people from the Runes. One translation was made by Henry Philips Junior round about 1875, and he felt that the Runes read either ‘Hako spoke to his men’ or ‘Hako’s son spoke to his men.”

Philips subsequently published a paper on it in 1884 according to a note made by Harry Piers, a former Curator of the Provincial Museum, and suggested that this Hako was a member of the Karlsefne Expedition of 1007.

In 1934 Eric Ruff also told Lionel & Patricia Fanthorpe (the author of The World’s Greatest Unsolved Mysteries) that Olaf Strandwold had translated the Runes on the stone. He was the County Superintendent of Schools in Benton County, Washington, and an eminent Norwegian scholar, who believed that the characters were certainly Runic. He interpreted them as: “Leif to Eric raises (this monument).”

Strange code stone?

When Olaf Strandwold did his work, George St Perrin was in charge of the stone and the Yarmouth Library then housed it. Georges’ explanation to Olaf in 1934 says clearly: “…shows very few signs of erosion. The cuts show, except in a fewisolated spots, a distinct V-shaped section…the stone is of very hard texture…the cuts are so well tooled that a highly tempered instrument must have been used by the inscriber…”

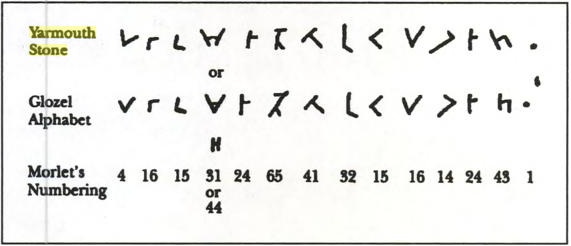

Strandwold search carefully through established Runic alphabets and locate known equivalents from authenticated sources which matched the Runes carved on to the Yarmouth Stone. He then laid these out in parallel with a third line below which gave the Latin alphabet’s equivalent of the Rune above. Strandwold took several closely cross referenced pages to establish and verify each of the fourteen Runes on the stone and finally came up with the Latin version:

LAEIFR ERIKU RISR

Allowing for the minor discrepancies between ancient Runic and Ogham characters carved at slightly different angles, there is also a remarkable similarity between the Glozel Alphabet from the central France, and the inscription on the Yarmouth stone:

In Viking history, Eric the red also known as Eric Thorvaldsson, fluorished in the closing years of the tenth century AD, as the founder of the earliest Scandinavian settlement Greenland. His son, Leif Ericsson (c. 970 – c. 1020) was a Norse explorer regarded was the first fully accredited European discoverer of North America (excluding Greenland), nearly 500 years before Christopher Columbus.

Originally posted 2016-08-22 12:32:22. Republished by Blog Post Promoter