Snakes were not always completely limbless.

The findings were based on new CT scans of Dinilysia patagonica – a relative of modern snakes which lived around 90 million years ago and grew up to two meters in length.

By comparing its interior canals and cavities with those of several modern species, the scientists were able to determine that burrowing animals exhibited a distinct inner ear structure that was different to that of animals which did not burrow at all.

By analyzing the fossils it became possible to find a correlation between the time at which snakes lost their limbs and the time at which they started to live and hunt in burrows.

“How snakes lost their legs has long been a mystery to scientists, but it seems that this happened when their ancestors became adept at burrowing,” said lead scientist Dr Hongyu Yi.

“The inner ears of fossils can reveal a remarkable amount of information, and are very useful when the exterior of fossils are too damaged or fragile to examine.”

Fresh analysis of a reptile fossil is helping scientists solve an evolutionary puzzle — how snakes lost their limbs. The findings show snakes did not lose their limbs in order to live in the sea, as was previously suggested.

Fresh analysis of a reptile fossil is helping scientists solve an evolutionary puzzle — how snakes lost their limbs.

The 90 million-year-old skull is giving researchers vital clues about how snakes evolved.

Comparisons between CT scans of the fossil and modern reptiles indicate that snakes lost their legs when their ancestors evolved to live and hunt in burrows, which many snakes still do today.

The findings show snakes did not lose their limbs in order to live in the sea, as was previously suggested.

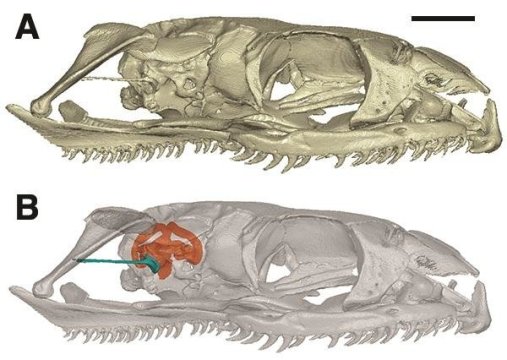

Scientists used CT scans to examine the bony inner ear of Dinilysia patagonica, a 2-metre long reptile closely linked to modern snakes. These bony canals and cavities, like those in the ears of modern burrowing snakes, controlled its hearing and balance.

They built 3D virtual models to compare the inner ears of the fossils with those of modern lizards and snakes. Researchers found a distinctive structure within the inner ear of animals that actively burrow, which may help them detect prey and predators. This shape was not present in modern snakes that live in water or above ground.

The findings help scientists fill gaps in the story of snake evolution, and confirm Dinilysia patagonica as the largest burrowing snake ever known. They also offer clues about a hypothetical ancestral species from which all modern snakes descended, which was likely a burrower.

The study, published in Science Advances, was supported by the Royal Society.

Dr Hongyu Yi, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, who led the research, said: “How snakes lost their legs has long been a mystery to scientists, but it seems that this happened when their ancestors became adept at burrowing. The inner ears of fossils can reveal a remarkable amount of information, and are very useful when the exterior of fossils are too damaged or fragile to examine.”

Mark Norell, of the American Museum of Natural History, who took part in the study, said: “This discovery would not have been possible a decade ago — CT scanning has revolutionised how we can study ancient animals. We hope similar studies can shed light on the evolution of more species, including lizards, crocodiles and turtles.”

Arindam loves aliens, mysteries and pursing his interest in the area of hacking as a technical writer at ‘Planet wank’. You can catch him at his social profiles anytime.