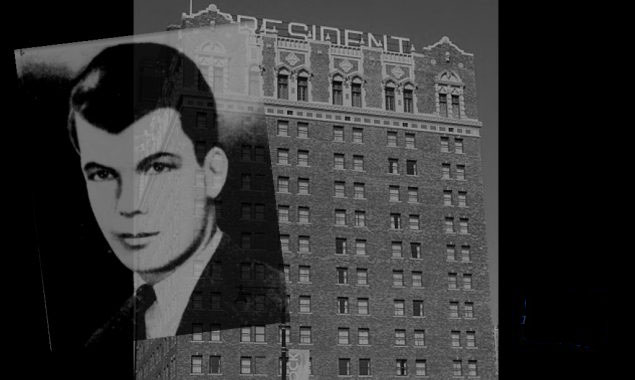

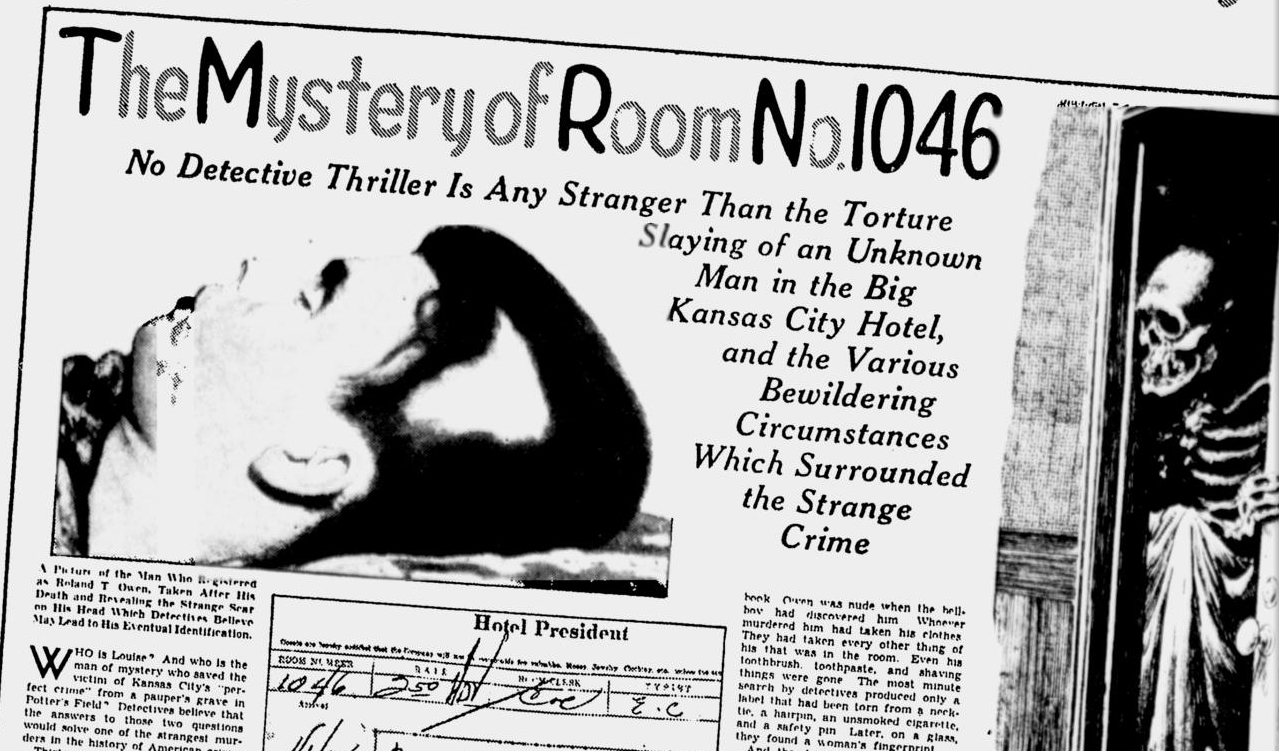

In Kansas City, Missouri, on the afternoon of January 2, 1935, a man walked into the Hotel President and asked for a room several floors up. He carried no luggage. He signed the register as “Roland T. Owen,” of Los Angeles, and paid for one day’s stay. He was described as a tall, “husky” young man with a cauliflower ear and a large scar on the side of his head. He was given room 1046.

On the way to his room, Owen told the bellboy, Randolph Propst, that he had originally thought to check into the Muehlebach Hotel, but was put off by the high price of $5 a night. When they reached 1046, Owen took a comb, brush, and toothpaste out of his coat pocket and placed them in the bathroom. Then, the pair went back out in the hall, where the bellboy locked the door. He gave Owen the key, after which the new guest left the hotel and the bellboy returned to his usual duties.

Later that day, a maid went to clean 1046. Owen was inside the room. He allowed her in, telling her to leave the door unlocked, as he was shortly expecting a friend. She noticed that the shades were tightly drawn, with only one small lamp to provide illumination. She later told police that Owen seemed nervous, even afraid. While she cleaned up, Owen put on his coat and left, reminding the maid not to lock the door.

Around 4 p.m., the maid returned to 1046 with fresh towels. The door was still unlocked, and the room still eerily dim. Owen was lying on the bed, fully dressed. She saw a note on the desk that read, “Don, I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait.”

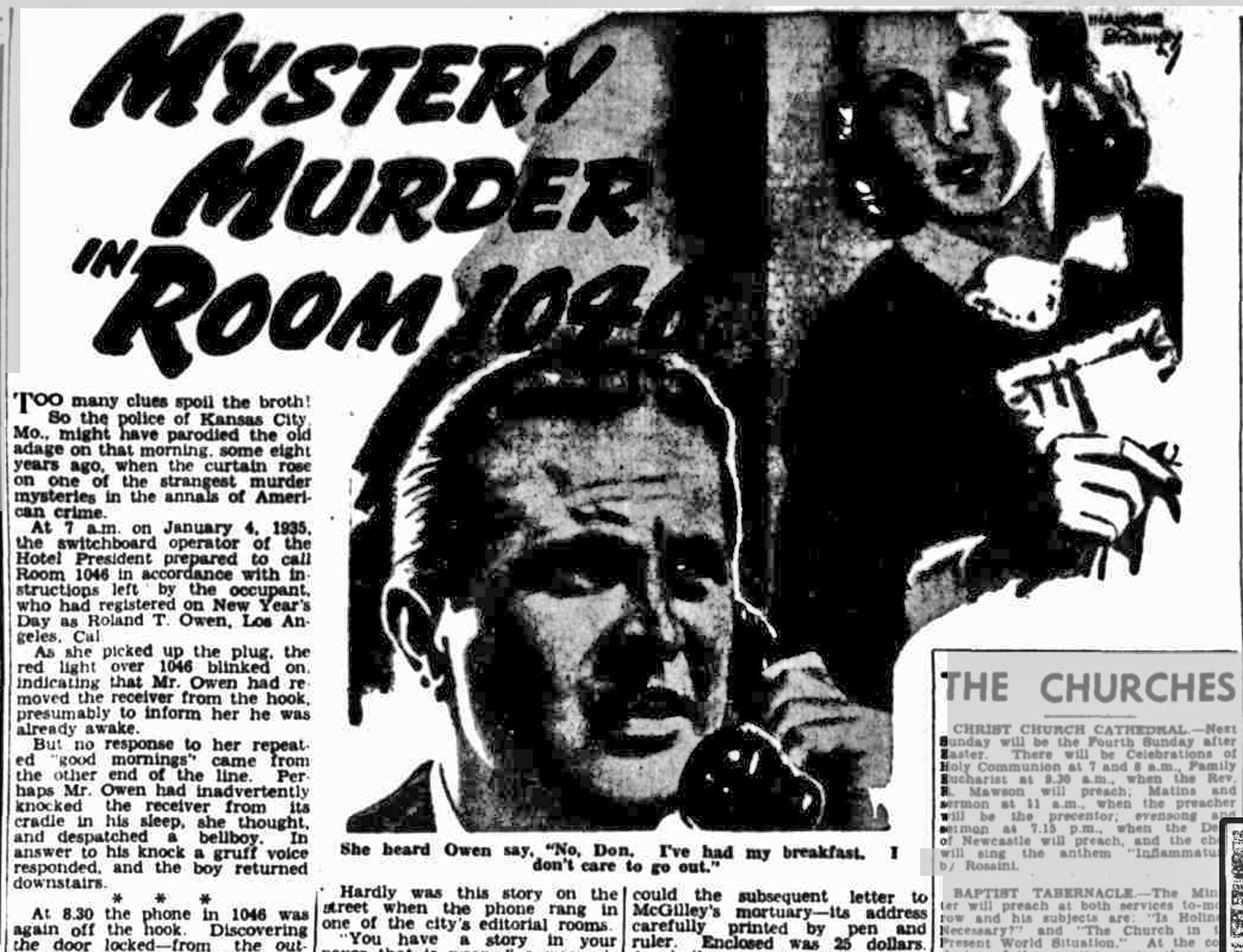

The next we know of Owen’s movements came at about 10:30 the next morning, when the maid came to clean his room. She unlocked the door with a passkey (something she could only do if the door had been locked from the outside.) When she entered, she was a bit unnerved to see Owen sitting silently in a chair, staring into the darkness. This awkward moment was broken by the ringing of the phone. Owen answered it. After listening for a moment, he said, “No, Don, I don’t want to eat. I am not hungry. I just had breakfast.” After he hung up, for some reason he began interrogating the maid about the President Hotel and her duties there. He repeated his complaint about the high rates of the Muehlebach.

The maid finished tidying the room, took the used towels, and left, no doubt happy to leave this strange guest.

Weird things in 1046

That afternoon, she again went to 1046 with clean towels. Outside the door, she heard two men talking. She knocked, and explained why she was there. An unfamiliar voice responded gruffly that they didn’t need any towels. The maid shrugged to herself and left.

Room 1048

Later that day, a Jean Owen (no relation to Roland) registered at the President, and was given room 1048. She did not have a peaceful night. She was continually bothered by the loud sounds of at least male and female voices arguing violently in the adjoining room. Mrs. Owen later heard a scuffle and a “gasping sound” which at the time she assumed was snoring. She debated calling the desk clerk, but unfortunately decided against it.

Charles Blocher, the graveyard shift elevator operator at the hotel, also noticed unusual activity that night. There was what he assumed was a particularly noisy party in room 1055. Some time after midnight, he took a woman to the 10th floor. She was looking for room 1026. He had seen her around the President numerous times–she was, as he put it discreetly, “a woman who frequents the hotel with different men in different rooms.”

A few minutes later, he was signaled to return to the 10th floor. The woman was concerned because the man who had arranged to meet her there was nowhere to be found. Being unable to help her, Blocher went back downstairs. About half an hour later, the woman summoned him again to take her down to the lobby. About an hour later, she returned to the elevator with a man. Blocher took them to the 9th floor. Around 4 a.m. the woman left the hotel, followed about fifteen minutes later by the man. This couple was never identified, and it is unknown what, if anything, they had to do with Owen and room 1046.

At about 11 p.m. that same night, a city worker named Robert Lane was driving on a downtown street when he saw a man running down the sidewalk. He was puzzled to see that on this winter night, the stranger was wearing only pants and an undershirt.

The man waved Lane down, thinking he was a taxi driver. When he saw his mistake, he apologized and asked if Lane could take him someplace where he could get a cab. Lane agreed, commenting, “You look as if you’ve been in it bad.” The man nodded and growled “I’ll kill that [expletive discreetly deleted in newspaper reports] tomorrow.” Lane noticed his passenger had a wound on his arm.

When they reached their destination, the man thanked Lane, then exited the car and hailed a cab. Lane drove off, having no idea that he had just played a minor role in one of his city’s weirdest murder mysteries.

The Owen case drifted into obscurity until late 1936, when a woman named Eleanor Ogletree learned of an account of the murder given in the magazine “American Weekly.” She thought the description given of “Owen” matched that of her missing brother Artemus. The Ogletrees had not seen him since he left his home in Birmingham, Alabama in April 1934 to “see the country.” The last his mother Ruby had heard from him were three brief, typewritten letters. The first of these notes arrived in the spring of 1935–several months after “Owen” died. Mrs. Ogletree later said she was suspicious of these letters from the start, as her son did not know how to type. The last letter said he was “sailing for Europe.” Several months after the last letter, she received a phone call from a man calling himself “Jordan. “Jordan” said that Artemus had saved his life in Egypt, and that her son had married a wealthy Cairo woman. When Mrs. Ogletree was shown a photo of “Owen,” she immediately recognized the dead man as her missing son. He was only 17 when he died.

The Owen case drifted into obscurity until late 1936, when a woman named Eleanor Ogletree learned of an account of the murder given in the magazine “American Weekly.” She thought the description given of “Owen” matched that of her missing brother Artemus. The Ogletrees had not seen him since he left his home in Birmingham, Alabama in April 1934 to “see the country.” The last his mother Ruby had heard from him were three brief, typewritten letters. The first of these notes arrived in the spring of 1935–several months after “Owen” died. Mrs. Ogletree later said she was suspicious of these letters from the start, as her son did not know how to type. The last letter said he was “sailing for Europe.” Several months after the last letter, she received a phone call from a man calling himself “Jordan. “Jordan” said that Artemus had saved his life in Egypt, and that her son had married a wealthy Cairo woman. When Mrs. Ogletree was shown a photo of “Owen,” she immediately recognized the dead man as her missing son. He was only 17 when he died.

The weird day

Around 7 a.m. the next morning, the President’s telephone operator noticed that the phone in room 1046 was off the hook. After three hours had passed without anyone placing the phone in its cradle, she sent Randolph Propst to tell whoever was there to hang up. The bellboy found the door locked, with a “Don’t disturb” sign out. When he knocked, after a moment he heard a voice tell him to come in. When he tried the door, he found it was still locked. He knocked again, only to have the voice tell him to turn on the lights. After a couple more minutes of fruitless knocking, Propst finally yelled, “Put the phone back on the hook!” and left, shaking his head at what he assumed was their crazy drunken guest.

An hour and a half later, the operator saw the phone was still unhooked. She sent another bellboy, Harold Pike, up to deal with the problem. Pike found 1046 still locked. He used a passkey to open the door–showing that it had again been locked from the outside. In the dimness, he was able to make out that Owen was lying on the bed naked. The telephone stand had been knocked down, and the phone was on the ground. The bellboy put the stand upright and replaced the phone.

Like Propst, he assumed their guest was merely drunk. He left without bothering to check Owen’s condition more closely.

Shortly before 11 a.m., another telephone operator noticed that the phone in 1046 was again off the hook. Once again, Propst was sent up to the room. He found the “Don’t disturb” sign still on the door. After his knocks got no response, he opened the door with his passkey and walked inside.

The bellboy found something far worse than mere intoxication. Owen, still naked, was crouched on the floor, holding his bloody head in his hands. When Propst turned on the light, he saw more blood on the walls and in the bathroom. The frightened bellboy rushed out and told the assistant manager, who summoned police.

Dreadful things

The officers found that about six or seven hours earlier, someone had done dreadful things to Roland Owen. He had been tied up and repeatedly stabbed. His skull was fractured from several savage blows. His neck was bruised, suggesting he had been strangled. Blood was everywhere. This small hotel room had been turned into a torture chamber. When questioned about what had happened, the semiconscious Owen only muttered, “I fell against the bathtub.” A search of the room found more strangeness. There was not a single stitch of clothing anywhere in 1046. The room’s standard soap, shampoo, and towels were also gone. All they found was a label from a necktie, an unsmoked cigarette, four bloody fingerprints on a lampshade, and a hairpin. There was also no sign of the cords which must have been used to bind Owen and the weapon that stabbed him. A hotel employee reported that several hours before Owen was found, he had seen a man and a woman leave the President hurriedly. There was no doubt that, in the words of one of the detectives, “someone else is mixed up in this.”

While Owen was being rushed to the hospital, he fell into a coma. He died later that night.

Meanwhile, investigators were quickly realizing that this was no ordinary murder. Los Angeles police found no record of any Roland T. Owen, which led to the assumption that the victim had checked in using a pseudonym. An anonymous woman phoned police the night of Owen’s death, saying that she thought the dead man lived in Clinton, Missouri.

“Owen’s” body was taken to a funeral home, where it was publicly displayed in the hope that someone could recognize him. Among the visitors was Robert Lane, who identified him as the peculiar man he had seen on the night of January 3. Several bartenders testified seeing a man matching “Owen’s” description in the company of two women. Police also discovered that the night before “Owen” registered at the President Hotel, a man matching his description had briefly stayed at the Muehlebach, giving his name as “Eugene K. Scott” of Los Angeles. Unsurprisingly, no trace of anyone by that name could be found, either. Earlier, Owen/Scott had stayed at yet another Kansas City hotel, the St. Regis, in the company of a man who was never identified.

They were having no more luck with tracing the “Don” “Owen” had talked to during his stay at the President. Was he the man who was there with the prostitute? Was he the strange voice who had told the maid not to bother bringing in fresh towels? Was “Don” the man “Owen” had told Lane he wanted to kill? Was “Don” the man who had been at the St. Regis with him? All excellent questions, which were fated never to be answered.

Nine days later

Nine days after “Owen” died, a wrestling promoter named Tony Bernardi identified the dead man as someone who had visited him several weeks earlier to sign up for wrestling matches. Bernardi said the man gave his name as “Cecil Werner.”

While all of this established that “Roland Owen” was a very peculiar man, none of it was the slightest help in discovering his real identity, let alone the name of his killer. The woman’s hairpin found in his room, plus the angry male and female voices Jean Owen had heard led to talk that the murder stemmed from a “love triangle,” but that theory remained mere speculation. Police were becoming resigned to writing off his death as one of the unsolved mysteries, and by the beginning of March, preparations were made to bury the John Doe in an unmarked grave.

However, before “Owen” could be brought to the city’s Potter’s Field, the head of the funeral home in charge of the body received an anonymous phone call. The man asked that the burial be delayed until money could be sent to cover the costs of a decent internment. The caller claimed that “Roland T. Owen” was the dead man’s real name, and that Owen had been engaged to the caller’s sister. The funeral director said that the mysterious benefactor told him that Owen “just got into a jam.” He added that the police “are on the wrong track.”

Shortly afterward, the cash arrived via special delivery mail–again anonymously–and “Owen” was finally buried in Memorial Park Cemetery. No one attended the funeral other than a handful of detectives. More money was sent with equal mysteriousness to a local florist to pay for a bouquet of roses for the grave. It was accompanied by a card to be placed with the flowers. It read, “Love forever–Louise.”

The Owen case drifted into obscurity until late 1936, when a woman named Eleanor Ogletree learned of an account of the murder given in the magazine “American Weekly.” She thought the description given of “Owen” matched that of her missing brother Artemus. The Ogletrees had not seen him since he left his home in Birmingham, Alabama in April 1934 to “see the country.” The last his mother Ruby had heard from him were three brief, typewritten letters. The first of these notes arrived in the spring of 1935–several months after “Owen” died. Mrs. Ogletree later said she was suspicious of these letters from the start, as her son did not know how to type. The last letter said he was “sailing for Europe.” Several months after the last letter, she received a phone call from a man calling himself “Jordan. “Jordan” said that Artemus had saved his life in Egypt, and that her son had married a wealthy Cairo woman. When Mrs. Ogletree was shown a photo of “Owen,” she immediately recognized the dead man as her missing son. He was only 17 when he died.

Unexplained mystery

The dead man had finally been identified. Justice for his brutal death, however, remained hopelessly elusive. This is one of those irritating unsolved murders that is nothing but a bunch of questions left in a hopelessly tangled mess. Why was Artemus Ogletree using multiple false names? What was he doing in Kansas City? Who killed him and why? Who was “Louise?” Who was “Jordan?” Who sent the money to pay for Ogletree’s funeral? Who really wrote those letters to Ruby Ogletree? What in God’s name happened in room 1046?

It’s almost certain we will never know. The investigation into Ogletree’s death was briefly reopened in 1937, after detectives noted similarities between his murder and the slaying of a young man in New York, but this also went nowhere. The case has remained in cold obscurity ever since, except for one strange incident about ten years ago. This postscript to the story was related in 2012 by John Horner, a librarian in the Kansas City Public Library who has done extensive research into the Ogletree mystery. One day in 2003 or 2004, someone from out-of-state phoned the library to ask about the case. This caller–who did not give his or her name–said that they had recently gone through the belongings of someone who had recently died. Among these belongings was a box containing old newspaper clippings about the murder. This caller mentioned that this box also contained “something” which had been mentioned in the newspaper reports. Horner’s caller would not say what this “something” was.

It seems only fitting that a case so mysterious throughout should have an equally baffling last act

Originally posted 2016-09-11 18:23:35. Republished by Blog Post Promoter