Imagine being stranded in the absolute middle of nowhere. A tiny speck of volcanic rock in the vast, churning blue of the South Pacific Ocean. You are thousands of miles from the nearest continent. There is no Home Depot. There are no cranes. There are no wheels. There isn’t even a single large tree left standing.

Now, look up.

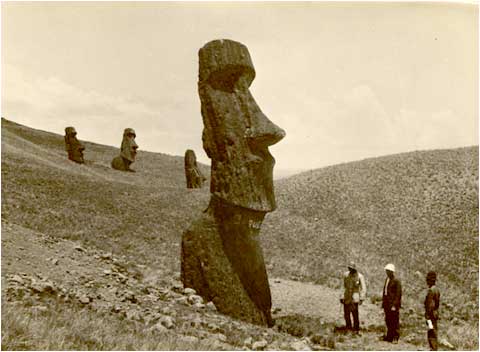

Towering over you is a face. A stoic, stone face weighing as much as a Boeing 737. It’s not just one face. It’s hundreds. They are watching the sky. They are watching the horizon. And they are guarding a secret that has driven scientists, historians, and conspiracy theorists absolutely bonkers for three centuries.

Welcome to Rapa Nui, commonly known as Easter Island. This isn’t just a travel destination. It is the site of the world’s greatest cold case. The statues, or moai, are the ultimate impossible object. We know they exist. We can touch them. But for the longest time, nobody could agree on how they got there.

The standard history books will tell you a polite story about logs and ropes. But when you really dig into the physics, the sheer weight, and the catastrophic history of this island, the polite story starts to crack. Let’s rip the lid off this mystery.

The Impossible Quarry: Rano Raraku

Here is a mind-bending statistic to kick things off. 95 percent of these behemoths came from a single spot: the Rano Raraku quarry. It is an extinct volcanic crater, a factory of the gods frozen in time.

When you walk into Rano Raraku today, it feels like the workers just clocked out for a lunch break and never came back. There are 397 statues still sitting there. Some are half-carved, sticking out of the rock face like trapped giants trying to pull themselves free. Others are buried up to their necks in sediment, the result of centuries of erosion sliding down the volcano.

But 288 of them escaped.

They made it to the ahus. These are the sacred stone platforms scattered around the island’s perimeter. The distance? Some of these multi-ton monsters traveled over 15 miles (25 kilometers). Over rough, uneven, volcanic terrain. Up hills. Down ravines. Around corners.

How?

Patricia Vargas, a heavyweight in this field and director of the Easter Island Studies Institute at the University of Chile, sums up the madness of it all. “When you have a massive production of these megalithic works on an island that is absolutely barren, with just grass, immediately it captures the imagination and you ask yourself ‘how did it all happen?’”

It’s the question that keeps you up at night. In Egypt, they had the Nile and massive armies of labor. In Stonehenge, they had flat plains. Here, on a tiny pimple of land in the Pacific, they moved mountains.

The Green Island Theory: A Paradise Lost

For decades, the biggest hole in the “log roller” theory was the landscape itself. You can’t roll a 50-ton rock on logs if you don’t have trees. And if you look at photos of Easter Island from the 1900s, it looks like a Scottish moor. Grass. Rocks. Sheep. No timber.

This led to some wild speculation. Did they use anti-gravity? Did aliens float them into place? Did they mold them out of ancient concrete (geopolymers)?

Vargas points out a critical pivot point in our understanding. “Until the early 1970s, no one talked about an island with a different environment until pollen analyses were made and until excavations were carried out in detail.”

Science finally caught up with the mystery. Researchers started drilling deep into the swampy mud of the crater lakes. What they found changed everything. They found pollen. Lots of it. And not just grass pollen.

Roughly between 1200 and 1600 AD—the golden age of statue building—Rapa Nui wasn’t a wasteland. It was a subtropical paradise. “There is certainty that the island had a wide variety of trees, including a huge type of palm that could get to be one metre wide,” Vargas explains.

This was the Jubaea palm, a cousin of the Chilean wine palm. These things were monsters. Thick, tall, and straight. The perfect rollers. They also had the hau hau tree, which has a fibrous bark that makes incredible rope. Strong enough to pull a truck. Strong enough to pull a god.

So, the materials were there. The crime scene had the weapon. But having a tree and moving a 70-ton rock are two very different things.

The “Walking” Legends: Fact or Fairytale?

If you ask the Rapa Nui people how their ancestors moved the statues, they don’t talk about rollers. They don’t talk about slaves dragging sleds. They smile and tell you the truth.

“The statues walked.”

According to oral tradition, the kings and priests used mana—spiritual power—to command the stone giants to walk from the quarry to their platforms. For centuries, Western explorers rolled their eyes at this. “Silly natives,” they thought. “Rocks don’t walk.”

But what if they were describing the method literally?

Look at the shape of the moai. They aren’t blocky. They have low centers of gravity. They have curved bellies (a shape scientists call D-shaped in cross-section). They are designed, intentionally, to be unstable in a very specific way.

Recent internet theories and experimental archaeology have started to back the “walking” theory. Not magic walking. Physics walking. Think about how you move a heavy refrigerator. You don’t pick it up. You tilt it, rock it to one side, twist, rock it to the other side, and twist. It “walks” forward.

We see drawings from a 1728 Dutch voyage that show standing moai. We see ropes. But were they dragging them flat, or guiding them upright?

The Drag-and-Roll Hypothesis

Despite the “walking” theory gaining ground recently, the “roller” theory has some heavy hitters behind it. Enter Jo Anne Van Tilburg. She is an absolute titan in Rapa Nui archaeology, hailing from UCLA.

She looked at the problem through the lens of a sailor. The Polynesians were the greatest voyagers the world had ever seen. They navigated the vast ocean in canoes while Europeans were still hugging their coastlines. They knew how to move heavy things.

“My personal theory is that they transported them using the same technology that the larger Polynesian community used to build, move, sail, and handle the large voyaging canoes,” Van Tilburg states. “What I have developed is a theory which suggests that using the tools, the technology and the engineering expertise of the ancient mariners, they were able to move and erect the statues.”

Here is the blueprint:

- The Sled: You strap the moai, lying on its back or stomach, to two massive parallel logs. This forms a rigid frame.

- The Crosspieces: You place smaller logs perpendicular to the runners.

- The Action: You roll the sled over the crosspieces. It reduces friction. It distributes weight.

It sounds great on paper. But could you actually do it? Van Tilburg isn’t an armchair theorist. In April 1999, she put her reputation on the line.

She gathered a team. They built a replica. They got the ropes. They got the people. And guess what? It moved.

“My experiment shows that it took approximately 40 people to move an average statue and 20 people to erect it. And that it could have been done in less than 10 days,” she says. The pride in her statement is palpable. 40 people. That’s it. You don’t need an army of ten thousand. You just need a village, some rope, and a lot of coordinated shouting.

But here is the catch. The “average” statue is one thing. But what about Paro? Paro was the largest statue ever moved and erected. It stood almost 10 meters (33 feet) tall and weighed 82 tons. Moving a Honda Civic is different than moving a tank.

The High-Tech Failure vs. Ancient Muscle

This is where the story gets ironic. And frankly, a little embarrassing for modern technology.

We think we are the pinnacle of civilization. We have iPhones, satellites, and hydraulics. But in the 1990s, we got a harsh lesson in humility.

In 1960, a massive tsunami slammed into Easter Island. It hit Ahu Tongariki, the grandest platform of them all. It tossed 15 massive moai around like bowling pins, scattering them inland, breaking them, burying them. It was a graveyard of giants.

In 1992, a restoration project began. Patricia Vargas and her team from the University of Chile wanted to stand them back up. But they didn’t use palm trees and ropes. They brought in the big guns. A Japanese crane company donated a massive, computerized hydraulic crane. State-of-the-art stuff.

You would think it would be a piece of cake. Lift. Plop. Done.

Wrong.

“We had a really modern, computerized crane – the most advanced in the world – and we had a lot of trouble,” Vargas admits. It wasn’t a weekend job. “In fact, it took us four years of work with a group of 40 people working day after day.”

Let that sink in. Four years. With hydraulics. The Rapa Nui people did this with rocks, wood, and fiber. And they did it hundreds of times.

This proves one undeniable fact: We have forgotten more about leverage and balance than we will ever know. The ancients weren’t primitive. They were engineering geniuses working with different materials.

The Suicide Theory: Did They Build Themselves to Death?

This brings us to the darkest part of the Easter Island saga. The “Ecocide” theory.

The island was once covered in palm trees. By the time the Europeans arrived on Easter Sunday in 1722, the trees were gone. The island was a grassland. The people were reportedly starving, living in a state of civil war, toppling each other’s statues in anger.

The popular narrative goes like this: The obsession with the statues became a mania. The chiefs needed bigger statues to show their power. Bigger statues meant more wood for sleds, levers, and canoes. They cut down the last tree to move the last stone.

Without trees, they couldn’t build canoes to fish in deep water. They couldn’t move statues. The soil eroded. Crops failed. Society collapsed into chaos and cannibalism.

It is a terrifying warning tale for our own planet. But is it true?

Recent studies suggest a different culprit: The Polynesian Rat. When the first settlers arrived, they brought rats (as food items). The rats had no predators. They exploded in population. What do rats love? Palm nuts. They ate the seeds before the trees could reproduce. The humans cut the trees, yes, but the rats prevented the forest from growing back.

It wasn’t necessarily a suicide pact. It was an invasive species disaster mixed with bad luck.

A Puzzle With Missing Pieces

Vargas refuses to lock herself into one single explanation. She is smart enough to know that history is messy.

“I think it depends on where the statue was going, the conditions of the terrain and also how big or fragile the statue was,” she argues. “In my mind, they were probably using more than one method.”

Maybe the small ones were dragged on sleds. Maybe the squat, heavy ones were “walked” with ropes, rocking side to side like a drunk giant stumbling home. Maybe they used methods we haven’t even dreamed of yet.

There are theories about greased paths made of mashed taro root. Theories about pivot points. Theories that the statues were moved fully upright, buried in mounds of dirt, and then dug out.

The Silent Watchers

Today, Rapa Nui remains a place of intense energy. You can feel it when you stand in the shadow of the moai. They are not just rocks. They represent ancestors. They represent a society that dedicated every ounce of its surplus energy to art and reverence.

Whether they rolled them on palm trunks or danced them down the road with ropes, the achievement is staggering. They turned a volcanic rock into a living god, and they moved it across an island without a single wheel.

Next time you struggle to move a couch into a new apartment with two friends, think about the Rapa Nui. Think about the 80-ton Paro statue. And remember: we might have the technology, but they had the will.

The mystery isn’t fully solved. And maybe, just maybe, it’s better that way.

Originally posted 2016-03-09 04:27:50. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

Originally posted 2016-03-09 04:27:50. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

Aloha, I’m Amit Ghosh, a web entrepreneur and avid blogger. Bitten by entrepreneurial bug, I got kicked out from college and ended up being millionaire and running a digital media company named Aeron7 headquartered at Lithuania.

![easter_island_head_old[1]](https://coolinterestingnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/easter_island_head_old1.jpg)