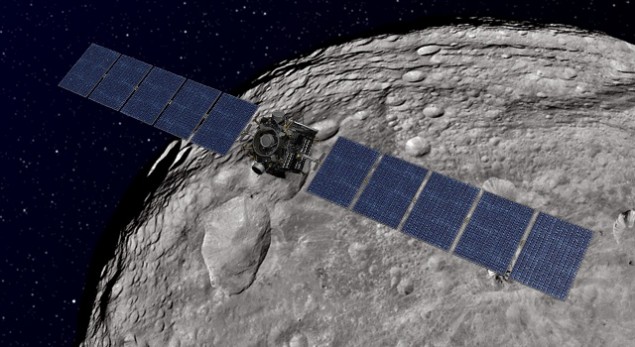

NASA Unable to explain the pyramid like structure spotted on Ceres have now sent the spacecraft Dawn in for a closer look.

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has moved in for a closer look at the dwarf planet Ceres. Since descending to an altitude of 900 miles in mid-August, its view has gotten three times sharper. That has allowed scientists to zoom in on a 4-mile-high mountain in Ceres’ southern hemisphere.

The cone-shaped peak, which is about as tall as Mt. McKinley (the tallest mountain in North America), has shiny sides that are composed of some kind of reflective material, possibly ice or maybe even steel.

The unexplained mountain pops out of a pretty flat region, and scientists aren’t sure how it got there. Recent ideas include the thinking that the pyramid could be artificial!

NASA are worried!

In an unexpected turn of events, NASA has now decided the pyramid needs further investigation. Dawn will descended to an altitude of 230 miles in December so the space boffins can get a closer look!

As the spacecraft gets closer, more and more features are beginning to reveal themselves.

This includes the mysterious bright spots, which appear now as an array of dots scattered across the floor of a crater – but their source remains unknown.

Just six months ago, Ceres appeared as nothing more than a few pixels of light to Dawn. Now it is nearing its closest orbit to the increasingly interesting dwarf planet.

By December of this year, the spacecraft will be just 225 miles (360km) above the surface – lower than the International Space Station is above Earth.

| For now, scientists must make do with these tantalising glimpses of the features that are waiting on the surface.In one new image, a pyramid-shaped peak is seen towering over a relatively flat surface.

The mountain is peculiar, as there are a few other features like it in the surrounding region – or even the rest of the dwarf planet. |

The structure is thought to rise about three miles (five km), which is roughly the height of Mont Blanc in France and Italy, the highest mountain in the Alps.

Another image reveals the bright spots in greater detail. Several can be seen next to the largest bright area, estimated to be six miles (9km) wide.

Ice and salt are the leading theories for what is causing this odd reflectivity.

‘It is exciting seeing these features come into sharper focus,’ Dr Marc Rayman, Dawn’s mission director and chief engineer, told MailOnline.

A few months ago, when Dawn began observing its new home from afar, we called it a bright spot. As the explorer closed in and provided better views, we realised it was two bright spots.

‘Now we see it is many. It’s still not clear what is causing these strong reflections, and I think still more data are needed.

‘Everyone has her or his own personal favorite theory, but the ultimate arbiter is nature. That is, we can all speculate, and we can offer arguments, but the answer is going to be clear soon.

‘My money is on the remnants from ice that has sublimated. The salts left behind then could be what’s reflecting the light.’

The mountain (seen here in another recent image) is peculiar, as there are a few other features like it in the surrounding region – or even the rest of the dwarf planet

The mountain (seen here in another recent image) is peculiar, as there are a few other features like it in the surrounding region – or even the rest of the dwarf planet Zooming in reveals the pyramid-shaped mountain in greater detail, but its formation and origin remains a mystery. These images were taken by the Dawn spacecraft in its second mapping orbit of Ceres, from a height of 2,700 miles (4,400km)

Zooming in reveals the pyramid-shaped mountain in greater detail, but its formation and origin remains a mystery. These images were taken by the Dawn spacecraft in its second mapping orbit of Ceres, from a height of 2,700 miles (4,400km)There is also evidence for past activity on the surface, including flows, landslides and collapsed natural structures.

Ceres appears to have more remnants of activity than the protoplanet Vesta, which the Dawn spacecraft studied for 14 months in 2011 and 2012.

Dawn, which arrived at Ceres on 6 March 2015, is the first spacecraft to orbit two separate bodies in the solar system.

It will remain in its current orbit until 30 June, before moving to a lower altitude of 900 miles (1,450km) by early August.

What are the bright spots?

Several theories are currently being touted for what the mysterious bright white spots are on Ceres.

The Hubble Space Telescope has found more than 10 on the surface, but Ceres has found that the two most prominent – ‘spot 5’ – are in a crater about 57 miles (92km) wide.

This image reveals the bright spots in greater detail. Several spots can be seen next to the largest bright area on the left, estimated to be six miles (9km) wide

This image reveals the bright spots in greater detail. Several spots can be seen next to the largest bright area on the left, estimated to be six miles (9km) wideAnother theory is that they are regions of ice, again reflecting sunlight.

Ceres is thought to have plenty of ice beneath its surface, which could be exposed when a asteroid or comet strikes the surface. The fact these bright spots are in a crater – where such an impact occurred – supports this theory.

| Another possibility is that they are cryovolcanoes – volcanoes that are shooting out water or ice.However, the lack of a raised area around the spots consistent with a volcano suggests this might not be correct.

And they could even be water vapour ejecting from a liquid reservoir under the ground, although again current observations – namely a lack of additional material near the spots – suggests this is not the case. |

‘The surface of Ceres has revealed many interesting and unique features,’ said Dr Carol Raymond, deputy principal investigator for the Dawn mission, based at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

‘For example, icy moons in the outer solar system have craters with central pits, but on Ceres central pits in large craters are much more common.

‘These and other features will allow us to understand the inner structure of Ceres that we cannot sense directly.’

Originally posted 2015-09-17 15:18:25. Republished by Blog Post Promoter