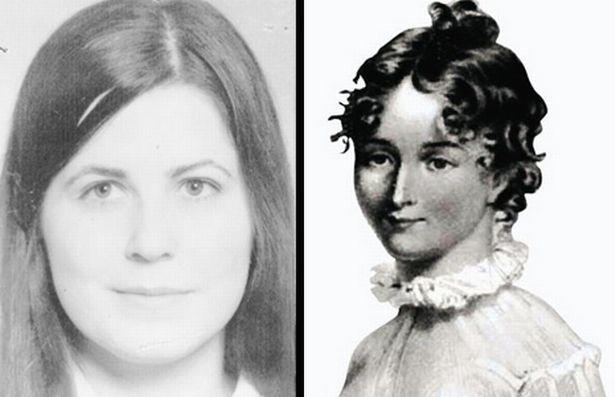

On 27 May 1817, the body of a murder victim – 20-year-old Mary Ashford was found in a flooded sandpit at Erdington, a village lying five miles outside of Birmingham in England. Exactly 157 years afterwards to the very day and hour of the Ashford murder, history repeated itself in a most brutal and chilling way when 20-year-old Barbara Forrest was strangled and left in the long grass near to the children’s home in Erdington where she was employed as a nurse. This may seem nothing more than a coincidence, but more intriguing similarities and parallels between the two murders came to light when the police were investigating the Barbara Forrest murder. As a police archivist officer read through the Ashford murder of 1817 he shook his head in disbelief. Whit Monday had been on 26 May both in 1817 and 1975 – the year of the Barbara Forrest murder. Like Ashford, Barbara Forrest had been raped before being murdered and both victims were found within 300 yards of one another. Ashford and Forrest shared the same birth date, and the coincidences didn’t stop there. Both girls had visited their best friend on the evening of the Whit Monday to change into a new dress for a local dance party. After each murder a suspect was arrested whose name was Thornton, and in both instances, this Mr Thornton was charged with murder but subsequently acquitted.

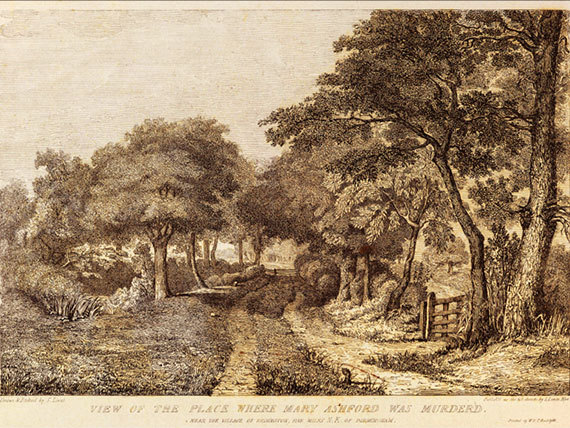

Let us take a closer look at these uncanny coincidences. At 6.30 a.m. on 27 May, 1817, a labourer on his way to work in Erdington came upon a heap of bloodstained clothes belonging to a woman, near to Penn’s Mill. He informed the police and during a search of the area around the suspicious find, they saw two tracks of footprints made by a man and a woman which led towards a flooded sandpit.

evidence and clues….

The police followed the two sets of footprints and saw that they ended at the edge of the water around the pit. The pit was searched and the corpse of a well-known and well-loved local girl named Mary Ashford was recovered. Her arms were heavily bruised and her clothing was bloodstained. Police made enquiries with the locals and soon established Miss Ashford’s last movements on the previous day. On Whit Monday – the 26 May – Mary had travelled from Erdington to Birmingham to sell dairy produce at the local market. She had then made arrangements to visit a friend’s house where she would change into a new dress. Then she and her friend – Hannah Cox – would go to the Whitsuntide dance at the Tyburn House Inn in the evening. Mary had arrived at her friend’s house at six in the evening. She changed into the new dress and then went to the dance with Hannah, and the two girls seemed to have enjoyed themselves, and they’d had no shortage of male admirers, although for a majority of the evening, Mary had been in the company of a young bricklayer named Abraham Thornton, while her friend had been dancing with a boy named Benjamin Carter. The dance ended around midnight, and the foursome headed towards their respective homes as far as a place known as the Old Cuckoo, which lay just a short distance from Erdington village. Hannah and Benjamin then separated from Mary and Abraham and went off in another direction.

Later on, about 3.30 a.m., Mary Ashford was seen walking towards the home of Hannah Cox’s mother. A witness mentioned that the girl was ‘walking very slowly and alone’. At the house of Hannah’s mother, Mary took of her new dress and changed into her working clothes. She told Hannah she was going home then said goodbye to her friend and left the house at 4 a.m. On two more occasions that morning Mary Ashford was seen. A Joseph Dawson testified that he had set eyes on the girl in Bell Lane around 4.15 a.m., and about ten minutes after that, Mary had been seen again in that same lane by Thomas Broadhurst. Both witnesses noted that Mary had been alone in Bell Lane.

Not long after these inquiries into Mary Ashford’s last movements, the police interviewed Abraham Thornton, who seemed in a state of shock after being told that Mary had been murdered, probably by strangulation – after being raped.

Thornton told detectives: ‘I cannot believe she is murdered; why, I was with her until four o’clock this morning.’

Thornton seemed sincere enough and apparently didn’t understand that he was the chief suspect in the murder investigation. However, he soon understood the situation when he was taken into custody later that day and searched. Detectives grilled him about every detail of events which unfolded after he had left Tyburn House Inn with Mary. Thornton admitted that he’d had sexual intercourse with Mary, but he denied he had raped and murdered the girl. In a deposition the bricklayer stated that when his friend Benjamin Carter and Mary’s friend Hannah Cox had left them, he and Mary had strolled hand in hand over a field to a stile. The couple sat talking for about fifteen minutes then went to the Green at Erdington where Mary went into her friend’s house to change her dress. Abraham had waited for quite some time but Mary did not come out so he went home alone. Thornton’s statement was backed up by three other witnesses who had seen him at that time. One witness, a gamekeeper named John Haydon, had even chatted to the young man for over quarter of an hour. The police continued their investigation into the murder of Mary Ashford, but came up against a brick wall. No one had seen the murder victim and Abraham Thornton together after they had been sighted at the stile at the top of Bell Lane at three in the morning, a fact which provided the police with a real headache.

The strange trial

Thornton was brought to trial in August that year at the Warwick Assize Court before Mr Justice Holroyd. Hundreds of people who believed Thornton had killed Mary Ashford had waited outside the courthouse from six in the morning. All of them hoped they’d be the first to hear that a verdict of guilty had been reached, but they were to be disappointed. After just six minutes of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’. In modern English law, that verdict would have been final but in the early 19th century an ancient law existed which enabled Mary Ashford’s brother William to appeal against the jury’s verdict and thus demand a second trial. This was duly done and upon 17 November 1817, Abraham Thornton once again stood in the dock, this time before Lord Ellenborough at the Court of the King’s Bench. By now, interest in the Mary Ashford murder had reached fever pitch in every corner of Britain, and the Fleet Street news hounds were delighted at a dramatic turn in the case. Legal history was made when Lord Ellenborough allowed Thornton to take advantage of an archaic law called ‘Trial by Battel’. This ancient right necessitated Thornton renewing his plea of ‘not guilty’ before throwing down a gauntlet from the dock. This signified a challenge to William Ashford for a fight to the death, unless one of them surrendered or was incapacitated during the fight.

There were objections to the Trial by Battel option, but Lord Ellenborough proudly enunciated to the court:

‘It is the law of England!’

If Ashford accepted the challenge and won, Thornton would be executed immediately, but if Thornton won, he would have to be freed and would no longer have to appear in court in connection with the Ashford murder.

Innocent?

Abraham Thornton held what resembled a heavy leather mitten with a trailing feather attached, and invoked the ancient English law. He declared he was innocent and that he was ready to defend his innocence with his body. He then lifted the gauntlet above his head, then hurled it down from the dock as the pressmen scribbled furiously.

William Ashford’s counsel disputed Thornton’s right to Trail by Battel and criticised Lord Ellenborough for allowing such an alternative to a proper second trial, but the protestations came to nothing. Because William Ashford had not responded to Abraham Thornton’s challenge by 21 April in the following year, the latter was thoroughly discharged. He would no longer have to stand trial for Mary Ashford’s murder, but because of the adverse publicity, no one would employ the bricklayer, so he later emigrated to the United States.

To this day, criminologists have tried in vain to determine who murdered Mary Ashford. Now for the facts of the eerie case which has strange echoes of the Ashford murder.

Discovery of another body

On 27 May, 1975, 20-year-old Barbara Forrest was found dead in the long grass of a ditch near Erdington. She had been strangled and raped, and her body, which was partly clothed, had lain undetected for over a week. Barbara had worked at the nearby Pype Hayes Children’s Home. Her facial features bore an almost identical similarity to Mary Ashford, and like Mary, Barbara had also been strangled after being raped. The police made inquiries and later arrested Michael Thornton, a Birmingham child care officer who worked at the home where Barbara had also worked. Like the Thornton who stood accused of murdering Mary Ashford in 1817, Michael Thornton was tried for the murder of Barbara Forrest, and he too was later acquitted. Both murders had taken place around the same time of day, and, furthermore, both victims had been to a friend’s house to change into a new dress before going out on the evening of Whit Monday to a dance.

Premonition

Stranger still, days before each victim was murdered, they made prophetic remarks about their impending fate. The week before Mary Ashford was murdered, she told Hannah Cox’s mother that she had ‘bad feelings about the week to come’, but was unable to elaborate on her unfounded sense of dread, and ten days before Barbara Forrest was raped and then strangled to death, she told a colleague at work of a strange premonition. Barbara’s words had been: ‘This is going to be my unlucky month. I just know it. Don’t ask me why.’

Were the ‘twin’ Erdington murders just a spate of uncanny coincidences, or were more sinister forces at work?

Originally posted 2016-11-03 17:06:49. Republished by Blog Post Promoter