Alien Worlds was published on a bi-monthly schedule by Pacific Comics from December 1982 to April 1984 (eight issues, including an offshoot Three Dimensional Alien Worlds published in July 1984). After Pacific went bankrupt, two final issues were published by Eclipse Comics in November 1984 and January 1985. In 1986, Blackthorne Publishing published their own one-shotAlien Worlds, with reprints of stories taken from earlier issues. In May 1988, Eclipse issued a standalone, unnumbered edition of the title as part of its Graphic Album Series, featuring all new stories and art.

Nearly all of the stories in Alien Worlds were written by Jones, with only a few exceptions (notably Jan Strnad’s “Stoney End” in Issue # 8 and Frank Brunner’s “The Reading!” in Issue # 9). Jones had developed a skill for the short genre tale, often with atwist ending, during his years with Warren Publishing while writing for their Creepy and Eerie titles. He was heavily influenced by the horror and science fiction movies of the 1950s, adding graphic violence and sexuality to the mix, complete with copious female nudity; several issues sported a “Recommended For Mature Readers” warning on the cover. However, for the most partAlien Worlds avoided the more intensely gruesome subject matter of Jones’ other Pacific comic, Twisted Tales, which was being published at the same time.

Front covers for the comic were by, among others, John Bolton, Dave Stevens, Frank Brunner, and Joe Chiodo. Contributing interior artists included Bolton, Stevens, Al Williamson, Richard Corben, Roy Krenkel, Val Mayerik, and Rand Holmes, as well as two stories written and illustrated by editor Jones himself.

In 1985, soon after the cancellation of Alien Worlds, Eclipse began publishing a similar science-fiction themed anthology, Alien Encounters. The title ceased publication in 1987 after fourteen issues.

Bruce Jones and actor Thomas Jane are writing a revival series slated for release sometime in the future.

As mountains go, Cerro Armazones may not be much to look at. Standing 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) tall, it is a shapeless reddish dust heap in Chile’s hot and arid Atacama Desert. The only sign of life is a dirt road zig-zagging all the way to the top.

But for astronomers like Joe Liske, this is arguably the world’s most interesting mountain right now, and not just because in the next few months more than 100 tonnes of dynamite will blow off its top to create a flat platform. By the early 2020s, that platform will become home to the biggest-ever eye on the sky, the E-ELT, or European Extremely Large Telescope.

With a mirror that is 39 metres (128ft) in diameter, the E-ELT will dwarf all existing optical telescopes – and those planned to appear in the next decade or two. And it won’t just bring plenty of life to this corner of the Atacama. The hope is that it will also help spot life out in the vastness of space.

In the past decade alone, astronomers have been discovering planets outside our solar system, or exoplanets, with astonishing speed. We now have identified nearly a thousand. Most are much bigger than Earth and almost certainly Jupiter-like gas giants, making making them quite unlikely for hosting life. None has so far been confirmed to bear life – even single-cell organisms – but some of these planets seem to be distinctly rocky and Earth-like: Kepler-62e, Gliese-581g and Kepler-22b, to name but a few.

“The quest for Earth-like exoplanets, and ultimately life on such planets, is one of the great frontiers of science, perhaps the last big piece in the puzzle of how we, humans, fit into the big picture,” says Liske, who works at the European Southern Observatory, an organisation that already operates a number of telescopes in the Chilean desert.

Two of the more high-profile planet hunters have hit rocky ground in recent months, however. The French-led Corot spacecraft, launched in 2006, greatly outlived its original two-and-a-half year mission of spotting terrestrial-sized exoplanets, but in November 2012, it suffered a computer malfunction, which made it impossible to send any data back to Earth. In June 2013, the French Space Agency announced it would switch the satellite off and let it burn up as it re-enters the atmosphere – the usual fate of our mechanical helpers in space.

Nasa’s $600 million space observatory Kepler, launched in 2009, has also been crippled recently. Kepler has helped spot thousands of potential exoplanets – over 130 of which have been confirmed – but two of its four reaction wheels that control the telescope’s direction have failed in recent months, and at least three are necessary to point it in the right direction. Kepler completed its primary mission in November 2012, and there are still thousands of candidates to sift through, but this month Nasa conceded that Kepler will no longer be able to search for exoplanets.

Thankfully, more planet-hunting missions are on the way, which will continue and even extend upon their legacy. Missions like the E-ELT, which Liske says “will completely revolutionise the exoplanet field.”

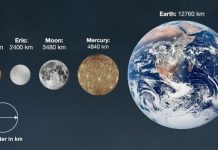

To be considered a “habitable” world, a planet has to be similar to Earth in size, rocky, and located in the so-called Goldilocks zone – an area of space around a parent star that is not too cold or too hot, but just right to support liquid water. Since these planets are expected to be small and faint compared to their sun, spotting them is tricky with existing ground-based optical telescopes.

![20130904-185551[1]](https://coolinterestingnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/20130904-1855511.jpg)