A Scotsman with an unlikely name, MacGregor made his fortune not by selling real things that didn’t belong to him, but imaginary things that didn’t belong to anyone. In the late 18th century, MacGregor managed to convince hundreds of wealthy investors that he was the “Cazique” or prince of Poyais, a land he had made up in modern day Honduras. He sold lands, titles and rights for the non-existent country to bankers, clerks, military men and other wealthy British personages. At one point, the sales he had amassed reached a staggering $2.12 million, which in today’s terms would equate to roughly $5.88 billion.

Not only this, MacGregor actually convinced his creditors to sail to the imaginary land and create a new life for themselves. He was successful in convincing seven ships’ worth of people – around 250 souls – to venture on the project. Predictably, it was a disaster; the first two ships suffered horrific deaths due to starvation and the other five were brought back. Hounded by his investors, MacGregor emigrated to Caracas, Venezuela, where he died in 1845.

The financial climate of the early 1820s was ideal for a con man. Napoleon had been defeated and the British economy was expanding steadily, driven on by manufacturing. The cost of living was falling, with industrial workers’ wages rising. Interest rates drifted down, with the government borrowing more and more cheaply. The country was in upbeat mood.

The downside to all this was that investing in government debt, a staple place to park spare funds, had become boring. The market rate on the most popular British government bond (the “consol”) fell steadily between 1800 and 1825. The government made the most of this, swapping its existing debt for new bonds that paid rates as low as 3%.

All this gave British investors the incentive and the confidence to look for more exciting opportunities

MacGregor rode this wave of optimism. In October 1822 he offered a £200,000 Poyais bond at 6%, a similar rate to that paid by the governments of Peru, Chile and Colombia. Unlike these countries, Poyais had no record of collecting taxes or system for doing so. But MacGregor argued that Poyais was so abundant in natural resources that export-tax revenue would easily cover the interest payments on the debt. And doubting investors only had to look at the Poyais settlement scheme for evidence that the plan was going ahead. It worked, and the bond was successfully floated. MacGregor’s funding was in place.

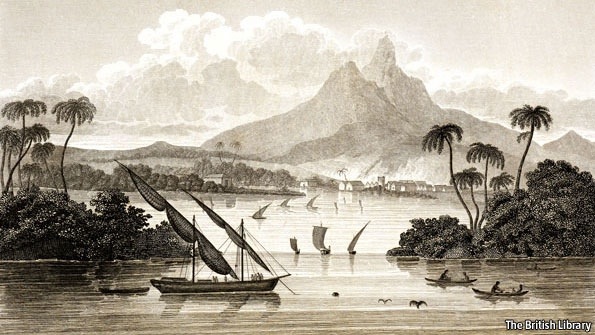

A new life in a distant land

MacGregor’s search for settlers was successful for different reasons. One was his aggressive sales pitch, described in “The Land that Never Was” (2004), by David Sinclair. It included interviews in the national papers, a book (supposedly written by Thomas Strangeways, but actually by MacGregor himself), and promises of friendly natives, a mild climate and fertile soil. Poyais’s forests were filled with valuable timber. It was strategically well placed near the Isthmus of Panama, with plans for a canal being mooted even in the early 1800s.

MacGregor’s prospectus would have found a natural audience in a public keen to start afresh abroad. Moving to the United States was as popular as buying stocks there. In the 1820s emigration to America, which had been held back by war, started to pick up again. MacGregor needed to persuade settlers that Poyais, a brand-new country, had more to offer than America did.

But some of the promises sounded very iffy. The natives were not only friendly, but loved the British. The soil was not just fertile, but capable of sustaining three maize harvests per year (elsewhere, two would be good going). The water supply was not just clean, clear and abundant, but in the streams of Poyais there were chunks of gold. How did the settlers, a group that included a banker, doctors and experienced military men, fall for this nonsense?