Amenhotep I from Ancient Egyptian “jmn-ḥtp” or “yamānuḥātap” meaning “Amun is satisfied” orAmenophis I from Ancient Greek Ἀμένωφις, was the second Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. His reign is generally dated from 1526 to 1506 BC. He was a son of Ahmose I and Ahmose-Nefertari, but had at least two elder brothers,Ahmose-ankh and Ahmose Sapair, and was not expected to inherit the throne. However, sometime in the eight years between Ahmose I’s 17th regnal year and his death, his heir apparent died and Amenhotep became crown prince. He then acceded to the throne and ruled for about 21 years.

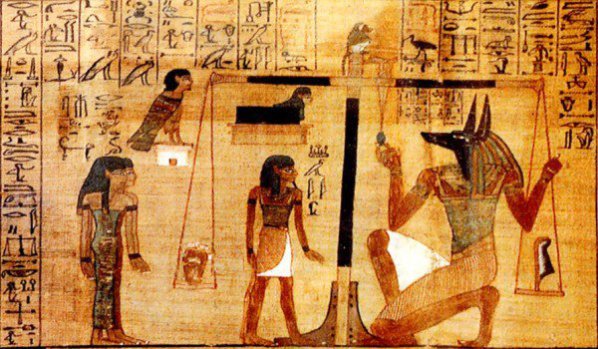

As well as the mummy cases, funerary statuettes, amulets and scarabs found in the pyramids, archaeologists also discovered “pyramid texts” provided for the use of the dead on their journey into the unknown. Written with reed pens on papyrus and often enclosed in wooden containers, or else inscribed on the walls of tombs or painted on the covers of coffins, these writings are known collectively as the Book of the Dead.

Whereas the household utensils unearthed in Egyptian tombs are essentially banal, these rich texts draw us deep into the realms of the unconscious, where we come face to face with the ancient world’s darkest, strangest, and most fearful imaginings.

Once mummification was completed and the mummy placed in the sarcophagus, a priest used an adze ritualistically to “open” the dead man’s mouth and enable his winged soul (ba) to enter and leave the mortal remains at will.

“Are you sure you want to see it?” she asks, holding a blank grey rectangular box. There is a boy’s foot inside the box. An ancient Egyptian boy’s blackened foot, minus one toe, sawn roughly from his leg at the ankle by Egyptian tomb robbers, a macabre relic of a time when London’s upper classes held mummy parties, champagne wing-dings built around the unwrapping of a 3000-year-old face. Dr Brit Asmussen, senior curator of archaeology at the Queensland Museum, isn’t amazed or repulsed by the foot, she’s saddened by it. “Someone had done that to them,” she sighs. “They stole their remains.”

Are you sure you want to see it? A question of death and ethics, a test of worth. Are you sure he was meant for your eyes, this boy buried before the gods? “It’s an interesting moral question,” Asmussen says, “the moral ethical obligations we have to the deceased.”

Time is relative in this room, the museum’s sprawling backroom collection vault, dark corridors of towering sliding shelves holding ancient Torres Strait turtle shell instruments, jars of fossilised parasites, prehistoric stones, Cyprian, Roman, Greek antiquities, mummified Egyptian hawks and a giant Papua New Guinean slip drum the size of a nuclear warhead. Perspectives on time collapse in this room. Asmussen holds the boy’s foot, maybe 3000 years old. She remembers when she was eight years old, trawling through a remainders pile in a Gold Coast bookstore, striking upon a Time-Life book on Neanderthals, Emergence of Man. She asked her father, a hard-working shift worker, to buy it for her and he did. At home, her father caught the wonder on her face as she stared wide-eyed into the book’s black and white 1950s photographs and introduced his girl to the glories of National Geographic, to the intrepid paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, to ancient Africa. That was 30 years ago but universal scale, and this boy’s foot, make 30 years ago seem like last week. The boy’s foot makes April 2012 seem like yesterday.

Asmussen slips on a pair of white cotton gloves. She walks on through the vault, takes a left turn into a corridor of shelving. She’s an archaeologist. It’s her job to trace moments in time, uncover and record the smallest details of objects, places, stories; pieces of the past’s backwardly expanding puzzle. She stops at a tall brown cupboard, pulls out a framed glass display case filled with fragments of ancient Egyptian papyrus, a hundred numbered and catalogued torn pieces, some the size of postage stamps, some like grains of pepper.

It’s an interesting moral question, the moral ethical obligations we have to the deceased.”

Of course she remembers the miraculous events of April 2012. She set those events in motion. She knows every small detail of that perfect and impossible moment in time when the 100-year international search for the last missing pieces of a prized and ancient Book of the Dead, belonging to an esteemed Egyptian builder named Amenhotep, ended in this very room. “One great big detective mystery,” she says, studying the papyrus beneath the glass, alive with Egyptian symbology, fragmented and strange images of animals and monsters and gods. Part of an instruction manual. “A collection of spells,” Asmussen says, “to help the deceased navigate the afterlife.” A book of magic.

Some archaeology romantics believe those final missing pieces wanted to be found. They say the series of events that led to their discovery was too preposterous to be anything but divine. The work of gods, they say, or Amenhotep himself, lingering in the afterlife, robbed long ago of the book that holds the key to his eternal paradise, left waiting, waiting, waiting for eight-year-old Brit Asmussen of the 20th century to find her book of archaeology in a Gold Coast remainders bin; waiting for her, many years later, to find four unidentified and unremarkable fragments of papyrus in a modest, unheralded museum in Brisbane, 14,350km from Egypt and 3400 years from the tears of his beloved wife Mutresti.

Missing pages of this famous book are still showing up in unexpected places.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead is one of the most famous books containing spells to be used in the afterlife. Rather than being a single book, it is more of a concept. The spells were usually written on the walls and on the bodies of the deceased. Upper class Egyptians were also given a papyrus scroll with the spells written on it, which would allow them to journey through the afterlife.??

Researchers have spent years trying to track down all the pieces of the Book of the Dead given to Amenhotep, a powerful Egyptian official from around 1400 BC. Nearly 100 fragments of this scroll were recently found – not in a sandy tomb, but in the basement of the Queensland Museum, where they were donated almost 100 years ago.??

Originally posted 2016-09-11 18:22:47. Republished by Blog Post Promoter