Building a new society in space

I like Star Trek as much as the next person. Probably more. But one thing has always bothered me: life on the Starship Enterprise may appear almost utopian but the way the ship – indeed the whole Federation is run – is essentially hierarchical. Humanity’s mission to “boldly go” is being undertaken by a quasi-military dictatorship. For a series originally billed by its creator as “wagon train in space”, it is hardly land of the free.

Is this really how we want to explore the cosmos and take our culture to the stars?

Now that there are proposals for private missions to the Moon, a plan to send a married couple to Mars and space agency ambitions to fly a crew of six into deep space to explore asteroids, this is no longer a theoretical question. If even only one or two of these schemes come to fruition, in the relatively near future, humans are going to be living in isolation beyond the direct influence of governments on Earth.

Later this year, a conference is being held in London on Extraterrestrial Liberty, looking ahead to a time when we may find ourselves – or our children – living in colonies on the Moon and Mars, or locked aboard a starship on a one-way trip to a distant star. If space technology continues to advance, human communities beyond the Earth would seem to be inevitable. As a result, people are already beginning to contemplate how these societies might operate.

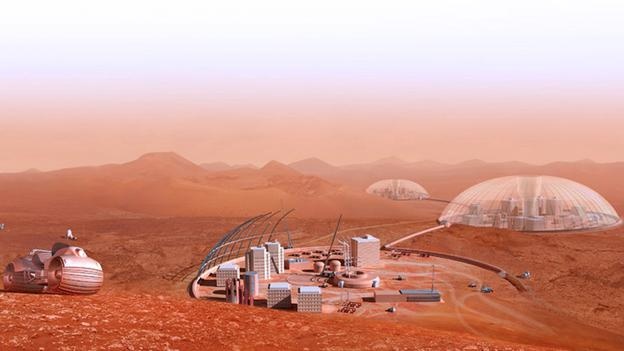

The man who has written the book – actually several books – on the colonisation of space is the founder and President of the Mars Society, Robert Zubrin. His proposals for the establishment of human settlements on Mars are exquisitely detailed, from the first landing to the eventual terraforming of the red planet for a thriving civilisation. The Mars Society currently operates Mars bases on Earth – in the Utah desert and Arctic – to simulate the challenges facing Martian colonists. Like the joint Russian-European Mars500 isolation experiment in 2011, where crewmembers were locked away for more than 500 days, these “missions” include a 15-20 minute time delay between the base and the control centre. Zubrin says the experiments have already given them hints about how extraterrestrial human civilisation might develop.

“One thing we certainly discovered with our simulated Mars missions is that you can’t command a crew from mission control,” he tells me. “The crew has to be led by the commander, generally operating with a very consultative style.” As a result, they have renamed their mission control “mission support”, acknowledging that they are no longer completely in charge. “I believe it will not be possible to control a Mars base from the Earth, increasingly the thing will take on a life of its own.”

Humanity test

It is a view shared by the Executive Director of the Institute for Interstellar Studies, Kelvin Long. As an engineer, his long-term goal is to develop plans for a starship but he sees the evolution of humanity into a spacefaring species as incremental. “I’m interested in huge space habitats, putting lots of people on space stations and sending them off to the stars,” he explains. “But you can’t do any of that unless you start with the small stuff and demonstrate that humans can live for sustained periods in space.”

So are humans up to the challenge – living 225 million kilometres (140 million miles) away, isolated from mission control as well as friends and family on Earth? When you share a house with someone and they fail to do the washing up, it’s a little annoying. Share a Mars base and someone fails to change the carbon dioxide scrubbers, everyone dies.

“Mars is the test for humanity,” Long says. “It’s the test of our character and, to me, that should be the next destination for the human species – to colonise Mars, to set up a small station and develop it gradually. If we can’t crack Mars, then forget everything else that we have ambitions for.”

The first people to visit Mars are likely to be selected for their skills and their emotional and physical suitability for the challenge. This will be a highly trained crew of “right stuff” astronauts, used to doing what they are told. But, predicts Zubrin, it will evolve. “The colony might start out as hierarchical, with a base commander and second in command, but the process of nature is going to take it in the direction of freedom.”

Things start to get really interesting when Mars explorers stay for years, rather than weeks, and the settlement becomes established. “People will have children… and at some point the Mars base breaks out of becoming a base and becomes an actual village – a real society with real people living real lives, with children in schools and community orchestras. All kinds of things that a base commander might think are completely extraneous.”

Read more: BBC science

Originally posted 2013-03-21 13:48:31. Republished by Blog Post Promoter