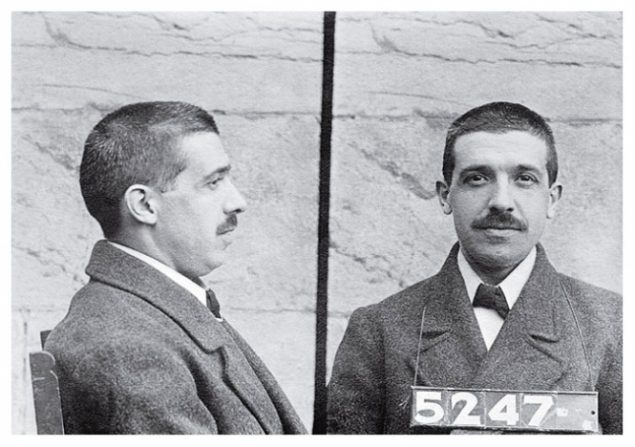

The Original Ponzi Scheme

Being a scam artist is bad enough; having a type of scam named after you is a perverse sort of immortality. consider the case of Charles Ponzi, who showed great chutzpah even by 1920s standards. Promising investors a return rate of 100% in just 90 days, Ponzi lured trusting thousands into his Security and Exchange Company, no relation to the Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates U.S. financial markets). But the supposed whiz kid merely used the new funds to pay off existing investors, a practice now known as the Ponzi scheme. the arrangement collapsed when the authorities began investigating, and after doing a stint in the slammer, “the Ponz’” finally got a real job – working for Alitalia, the Italian national airline.

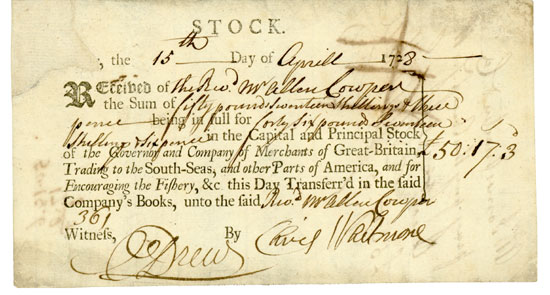

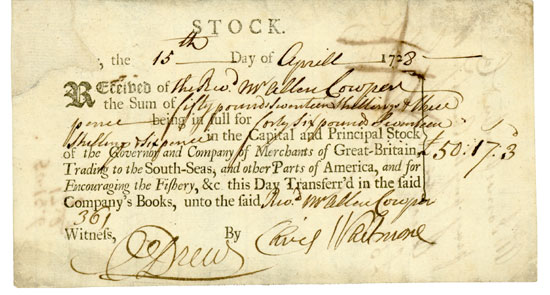

The South Sea and Mississippi Bubble

Don’t you just love globalization? In the early 18th century this double bubble grew on both sides of the English Channel at the same time, probably the first example of globalization in financial markets. In England, investors snatched up shares of the South Sea Company, a firm that was supposed to monopolize trade with the Americas, while in France money flowed into a company set up by Englishman John Law to operate in the Mississippi Valley and other French colonial areas. Share prices of the companies rose so much that it became necessary to invent a new word for those who grew rich in the bubble: =. somehow the South Sea Company never made a profit; claims that Louisiana had mountains of gold turned out to be a little less than accurate. After share prices collapsed in 1720, France had a government crisis, and England passed the Bubble Law, forbidding companies to issue stock.

Florida’s Real Estate Boom

President Andrew Jackson – whose face graces the $20 bill – won Florida for the United States in 1821, but for 100 years Americans couldn’t quite figure out what to do with it (aside from removing the Native American population). But in the early 1920s developers descended en masse on the Sunshine State, realizing its potential as a giant vacationland for winter-weary northerners. A huge boom ensued, with prices rocketing to $1,000 per acre, a hefty sum of money in those days. At one point, an amazing one-third of Miami’s population had become real estate agents. Right idea but bad timing – Florida weather helped burst the bubble with severe hurricanes in 1926 and 1928.

The Roaring ‘20s Stock Market

In the 1920s stocks could be purchased like real estate, by putting 10% down and taking out a 90% loan from the broker, secured by the value of the shares. This huge margin provided fantastic leverage – when stock appreciated. And appreciate they did. The Dow Jones industrial average rocketed 344% between 1923 and 1929, and more and more Americans got caught up in the stock market frenzy. It was not all speculation or a pyramid scheme: there were legitimate reasons for investors to be optimistic. The ‘20s were a period of rapid economical growth and development of new technologies: radio, electricity, automobiles, and airplanes. Nevertheless, the bubble burst in October 1929, and the Dow lost nearly 25% in just two days. The crash was promptly followed by the Great Depression, and the market bottomed a few years later, at just 11% of its 1929 peak.

Japan’s Stock Bubble

In the 1980s Japanese companies could do no wrong, as far as investors were concerned. the Nikkei 225 index of the Tokyo stock market rose dramatically throughout the decade – dipping briefly only during the 1987 Black Monday crash – to hit almost 40,000 in 1989. Its market capitalization peaked at 611 trillion yen – larger than the New York Stock Exchange’s. So convinced was everybody that stock prices had nowhere to go but up, Japanese stockholders offered their big clients guaranteed returns on their stock portfolios. It all came to an end when growth in Japanese exports failed to keep pace with investors’ expectations, an for over 10 years the Nikkei slumped – ultimately giving up all the gains of the late 1980s and returning to the pre-bubble level of around 7,800 in early 2003.

Russia’s Notorious MMM

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Russians were naive about financial markets. So, when in 1994 an obscure company called MMM (not to be confused with the 3M Company, the American blue chip) opened offices in Moscow and other Russian cities and began offering fantastic returns on its shares. Russians pulled their hard-earned rubles out of their mattresses. they didn’t ask how MMM was going to earn such returns after years of Communist propaganda, they had an unshakable faith in the capitalist system. Sergey Mavrodi, MMM’s founder, even got elected to the Russian parliament. The damage from the pyramid was relatively small; when the scheme collapsed in 1995, MMM had stolen an estimated 4100 million, a mere pittance by the standards of Enron. But the number of Russians taken in was enormous, since record keeping was spotty, estimates ran as high as 50 million – which would make it the largest fraud of its kind in history.

The Internet Bubble

American investors have none of the excuses the Russian investors had. They’re supposed to be the hard-nosed capitalists and the most sophisticated investors in the world. But in the second half of the 1990s they got caught in the Internet bubble on NASDAQ. This wasn’t all that different from a pyramid scheme, even though it was touted by hotshot analysts working for the world’s most respected investment banks. Internet companies that never made a profit were valued by the market at hundreds of times their annual revenues. The NASDAQ composite index, which traded at 1,500 in 1998, rocketed to over 5,000 by March 2000, and serious analysts began measuring the number of mouse clicks visitors made at different Web sites. As in other bubbles, though, the fall was precipitous, and the shares of those few Internet start-ups that survived fell to a tiny fraction of their peak values.

Originally posted 2016-09-07 02:01:39. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

Arindam loves aliens, mysteries and pursing his interest in the area of hacking as a technical writer at ‘Planet wank’. You can catch him at his social profiles anytime.