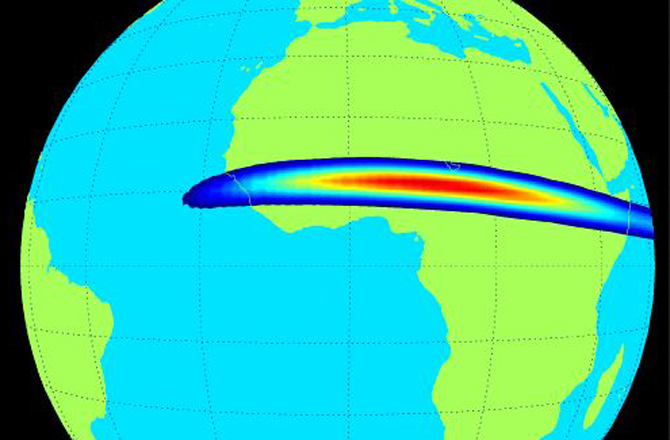

The equatorial electrojet is a natural current about 60 miles above the surface of the Earth. New findings suggest that it amps up more than ever suspected and could be disturbing electrical grids near the equator.

It doesn’t make compasses needles spin wildly or have anything to do with the lost city of Atlantis, but scientists have discovered a truly unearthly force they suspect is messing with electrical grids near the equator.

It’s called the equatorial electrojet: a seemingly innocuous current of electrons and ions 60 miles (100 km) above the ground, in Earth’s ionosphere.

New research shows that when even a mild shock wave in the solar wind hits the Earth, it can suddenly amp up the equatorial electrojet and create localized magnetic storms – smaller versions of the large geomagnetic storms that have knocked out power grids and charged up and damaged long pipelines under the aurora-lit skies of higher l

“Earth’s magnetic field is like an umbrella on a windy day,” said Brett Carter a space physicist at RMIT University’s SPACE Research Centre in Australia. “As the wind changes the umbrella flops around.” The places most sensitive to abrupt solar wind changes – called interplanetary shock waves – are near high latitudes and the equator.

“We’re not talking about doomsday-style events,” said Carter, who is the lead author of a paper reporting the discovery in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. But the very idea of any space weather effects on the ground so far away from the Earth’s poles is rather new.

The equatorial electrojet’s tendency to act up was discovered by analyzing 14 years of ionospheric data from around the world. Carter and his colleagues found that the current can be amplified by even small interplanetary shock waves from the sun encountering Earth’s magnetic field – shock waves that are too weak to trigger high latitude geomagnetic storms.

That means the equatorial space weather revs up a lot more frequently than at high latitudes. The milder but more frequent magnetic storms from the equatorial electrojet storms could be causing problems in electrical grids and pipelines in places like Africa, South America, Southeast Asia and southern India, say the researchers.

“The reason people have not been focused on it in the past is because the large stuff usually happens afterwards,” said Carter, of the typical passage of a powerful interplanetary shock wave. Those large, high latitude events drew attention away from the equator. It has also taken longer to equip equatorial regions with instruments to study how the equatorial electrojet behaves, he explained.

But now that are getting a clearer picture of what might be happening. The magnetic storms essentially turn any large electrically conductive structures – like electrical grids and pipelines – into part of a giant natural electrical generator. The currents disturb the power already in the grids, and can cause corrosive chemical reactions in pipelines.

“It’s complicated,” Carter said of the ways that magnetic storms cause trouble. You have on current being put on top of another, pushing it in one direction. “It could be adding to it in one place and taking it away in another.” On top of that it’s changing minute-by-minute, and so managing the fluctuations in a grid is not easy. “It’s like trying to balance an umbrella on your hand.”

Could Gas Explosions Explain Bermuda Triangle Mystery?

Scientists do not know precisely how the equatorial electrojet has affected grids in equatorial regions because they have not yet worked with the power companies there, said Antti Pulkkinen, a research astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who also studies the equatorial electrojet. But papers like this one could help to convince local power companies to share what they see happening in their grids, he said.

“We’re trying to make connections to African countries,” said Pulkkinen. “It’s still largely to be explored.”

The matter might take on added importance if proposals for “super grids” ever take off. The proposed European super grid would connect Europe to north Africa, which is more susceptible to the equatorial electrojet.

“People are moving forward with (super grid plans) with the assumption that equatorial region is free of space weather problems,” said Carter. But this research shows it’s clearly not the case.

Originally posted 2015-10-15 03:49:31. Republished by Blog Post Promoter