ASTONISHING CASES

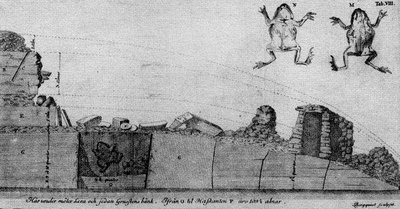

Toad in a stone.

In 1761, Ambroise Pare, physician to Henry III of France, related the following account to the Annual Register: “Being at my seat near the village of Meudon, and overlooking a quarryman whom I had sent to break some very large and hard stones, in the middle of one we found a huge toad, full of life and without any visible aperture by which it could get there. The laborer told me it was not the first time he had met with a toad and the like creatures within huge blocks of stone.”

Toad in limestone.

In 1865, the Hartlepool Free Press reported that excavators working on a block of magnesium limestone taken from about 25 feet underground near Hartlepool, England, discovered a cavity within the stone that contained a live toad. “The cavity was no larger than its body, and presented the appearance of being a cast of it. The toad’s eyes shone with unusual brilliancy, and it was full of vivacity on its liberation. It appeared, when first discovered, desirous to perform the process of respiration, but evidently experienced some difficulty, and the only sign of success consisted of a ‘barking’ noise, which it continues to make invariably at present on being touched. The toad is in the possession of Mr. S. Horner, the president of the Natural History Society, and continues in as lively a state as when found. On a minute examination of its mouth is found to be completely closed, and the barking noise it makes proceeds from its nostrils. The claws of its fore feet are turned inwards, and its hind ones are of extraordinary length and unlike the present English toad. The toad, when first released, was of a pale colour and not readily distinguished from the stone, but shortly after its colour grew darker until it became a fine olive brown.”

Toad in a boulder.

Around the same time, an article in Scientific American related how a silver miner named Moses Gaines found a toad inside a two-foot diameter boulder. The article stated that the toad was “three inches long and very plump and fat. Its eyes were about the size of a silver cent piece, being much larger than those of toads of the same size as we see every day. They tried to make him hop or jump by touching him with a stick, but he paid no attention.” A later article in Scientific American said: “Many well authenticated stories of the finding of live toads and frogs in solid rock are on record.”

Lizard revives.

In 1821, Tilloch’s Philosophical Magazine wrote how David Virtue, a stone mason, was working on a large chunk of rock that had come from about 22 feet below the surface when “he found a lizard embedded in the stone. It was coiled up in a round cavity of its own form, being an exact impression of the animal. It was about an inch and a quarter long, of a brownish yellow color, and had a round head, with bright sparkling projecting eyes. It was apparently dead, but after being about five minutes exposed to the air it showed signs of life. It soon ran about with much celerity.”

Toad and lizard in solid rock.

During World War II, a British soldier was working with a team in the quarrying of stone for making roads and filling in bomb craters. They often used explosives to crack open the rock. After one such detonation, the soldier pried a stone slab away from the quarry face when he saw “in a pocket in the rock a large toad and beside it a lizard at least nine inches long. Both these animals were alive, and the amazing thing was that the cavity they were in was at least 20 feet from the top of the quarry face.”

MORE AMAZING CASES

Live toads and frogs have also popped out from inside impossible tight and enclosed spaces within trees that were being cut open:

Toad in an elm tree. The French Academy of Sciences published an account in a 1719 edition of it Memories of the felling of a large elm tree. In the exact center of the trunk, about four feet above the root, was found “a live toad, middle-sized but lean and filling up the whole vacant space.”

68 toads in a tree. The Uitenhage Times of South Africa in 1876 printed the experience of timbermen who were cutting a tree into planks, when deep inside of it a hole was found containing 68 small toads, each about the size of a grape. “They were of a light brown, almost yellow color, and perfectly healthy, hopping about and away as if nothing had happened. All about them was solid yellow wood, with nothing to indicate how they could have got there, how long they had been there, or how they could have lived without food, drink, or air.”

Odder still, it is not just natural stone and trees in which these impossibles occur:

Toad in a plaster wall.

When a castle wall was being demolished in September 1770, a live toad was plucked from the solid plaster. That wall had stood undisturbed for more than 40 years.

Frogs in a concrete floor.

Renowned biologist Julian Huxley received a letter from a gas fitter in Devonshire, England, who had broken up some concrete flooring to install some pipe extensions: “My mate was at work with a sledge hammer when he dropped it suddenly and said, ‘That looks like a frog’s leg.’ We both bent down and there was the frog. [The] sledge was set aside and I cut the rest of the block carefully. We released 23 perfectly formed but minute frogs which all hopped away to the flower garden.”

Turtle in concrete.

In 1976, a Fort Worth, Texas construction crew was breaking up some concrete they had set just a year before. Within the broken concrete, a living green turtle was found in an air pocket that matched the shape of the creature’s body. If it had somehow got in when the concrete was poured a year earlier, how did it survive over that time? Ironically, the poor turtle died a few days after its release.

There are no easy explanations for these incredible anecdotes. Those who found the creatures nearly always state that there was no discernable way – no small hole, crack, or fissure – by which they could have gotten into these pockets inside the rock. And the pockets are always about the exact size of the animals within – some even bearing an impression of the animal, as if the rock had been cast around it. Even if a fertilized egg of a toad or frog had somehow seeped into the rock cavity, what did it live on? What did it eat, drink and breathe to grow, in some cases, to full size? Being unable to move inside the rock, how did its muscles develop so that it could hop away upon being released? Geologists tell us that rock is formed over thousands of years. How old are these animals?

The most incredible of such anecdotes was recorded in 1856 in France. Workmen laboring in a tunnel for a railway line were cutting through Jurassic limestone when a large creature stumbled out from inside it. It fluttered its wings, made a croaking noise and dropped dead. According to the workers, the creature had a 10-foot wingspan, four legs joined by a membrane, black leathery skin, talons for feet, and a toothed mouth. A local student of paleontology identified the animal as a pterodactyl!

Originally posted 2014-01-21 22:25:23. Republished by Blog Post Promoter

![20140121-232111[1]](https://coolinterestingnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/20140121-2321111.jpg)